Help us protect the commons. Make a tax deductible gift to fund our work. Donate today!

Last year, after a series of attacks on refugee centers in Berlin, I saw a Facebook post circulating from my friend Paul Feigelfeld, an academic in Berlin. The post called on his community – academics, artists, translators, and activists – to take action to stop the continued attacks on asylum seekers in Europe. That post and others like it were the spark for Refugee Phrasebook, a CC0 open data project with hundreds of contributors. Taking shape over the past year, the book has spread all over Europe, attracting global press in Wired, Newsweek, STERN, Die Zeit, and Der Spiegel, as well as winning the Prix Ars Electronica “Award of Distinction” for Digital Communities.

With 1.1 million asylum seekers in Germany, the need for language and education support is acute, and the Refugee Phrasebook helps meet that need. As both a physical and digital resource for refugees, the project has spread rapidly across Europe, and contributors are adding more languages, data, and phrases to continue to support an increasing number of refugees.

Refugee Phrasebook is accepting contributors who want to get involved and collaborate with organizations like the P2P Foundation, CC, and Wikimedia. Visit their website to contribute to their global knowledge community.

What was the impetus for the Refugee Phrasebook? How did the project come about?

The urgency of the refugee situation in the summer of 2015 made it immediately clear that language aids were needed for both refugees and helpers. Infrastructure was bad, people had short battery life on their smartphones – if they had one at all – or no data plans to use translation apps, so along with many other small simple projects, a shared document with often used phrases for basic communication and central questions spread over several Facebook groups.

It grew exponentially and was quickly transformed into a Google spreadsheet to make the data easier to expand and maintain. Hundreds of people contributed; there were anonymous contributors, brief contributors, and others on a more long term basis. People started creating the first print versions after only a few days and distributed them at train stations in Vienna or Berlin. It soon found its way to Lesbos, Idomeni, and even Norway. It spread very quickly and received a lot of positive feedback and support from private individuals and institutions like universities, art schools, and art institutions, who provided printers, design expertise, etc.

How did the Refugee Phrasebook evolve from nascency to a global project of this size? What kinds of tools, both digital and physical, helped you scale the project so rapidly? How do you organize the data and translations?

The Google spreadsheets were shared only on Facebook at first, but soon it became clear that we needed more translators beyond the initial group based in Berlin. We created a website as a contact point for contributors, and thanks to Open Knowledge Foundation Deutschland e.V., we could also handle donations and provide an official donation receipt. As the media woke up to the topic, our website was also covered a lot, which helped to reach other initiatives.

To coordinate the project, we mostly use Skype or Zoom calls, Etherpads, Slack, and Trello. In several hackathons, developers helped to improve the structure of the tables and how to display them on the site. But the main factors were a strong sense of urgency, the network effect of personal recommendations, and the data being open, which is still exceptional in this field.

How do the physical and virtual interact in this project as both a virtual collection of data as well as a collection of physical booklets?

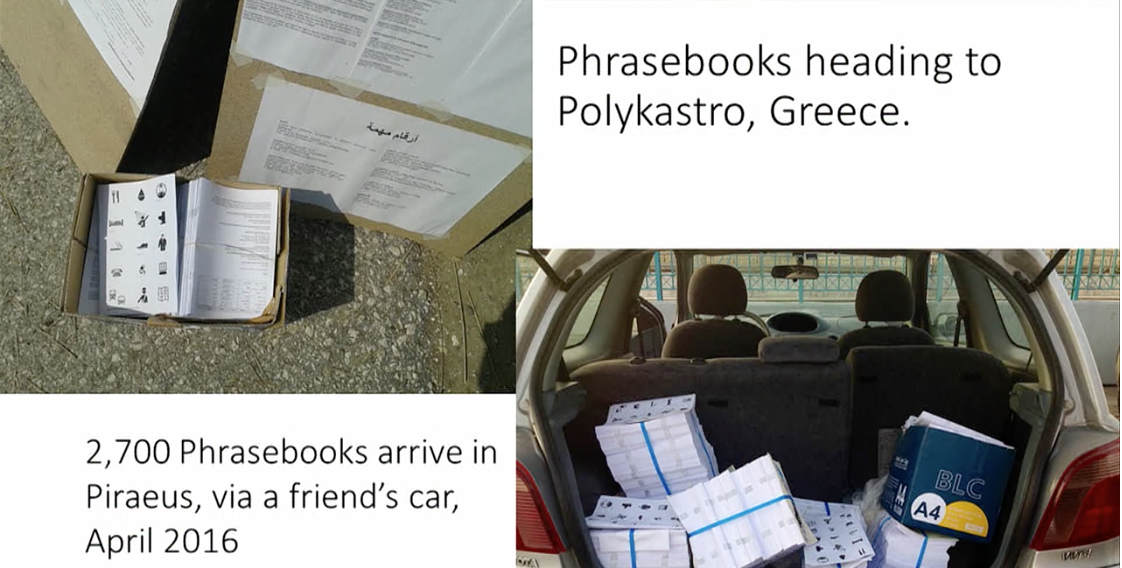

It continues to be interesting how virtual and physical realms overlap in this project. First, of course, there are very pragmatic practical problems that arise: how can we create a layout that fits as much information as possible in the best way onto as few pages as possible to keep costs down? Where can we print? This is always done differently: everyone can use the data and create and print their own booklets, or download existing print versions from our website, but often we collaborate with the people who need booklets, help raise money for printing costs, locate affordable printers, organize transport and distribution. Creating the phrasebook alone from data to print to distribution and usage is already an act of conversion and conversation.

All these aspects give us valuable feedback on how to make things easier, where the data is inconsistent, what is lacking in terms of phrases, languages, information and so on. At the moment, we are working on making the conversion from language data in the spreadsheets to printed booklets easier, so people can simply select what they want and don’t have to go through tedious conversion processes. Refugee Phrasebook is a tool for places with the worst infrastructure, which is why it has also been used as insulation during cold weather and to kindle fires. It’s a simple and versatile resource. In this case, it can be helpful to burn books.

What kinds of outcomes have you seen from sharing the data under CC0? Has the use of CC been particularly relevant in terms of your work and what you are setting out to do?

Thanks to the open CC0, the translations could be used in several apps and other translation projects. Designers used it to create signs and other communication aides, local initiatives created custom print versions.

Being able to adapt the content to a specific use was especially important for the camps, as refugees encountered different languages across Europe and often could only stay for a few days. In a situation that required urgency, we wanted everyone to be able to adapt and share the translations freely. We will continue to share content under a CC license.

The next step is an automatic solution to create custom pdf files as well as more icons.

What kinds of outcomes have you seen from this project, more generally? How have you balanced the project’s growth in terms of the usage of the physical and virtual assets as well as the ever expanding scope of a project such as this one?

The demand for print versions was a surprise at first, but electricity and wifi is often not available in refugee camps and shelters. A decentralized structure with independent and connected regional projects helped develop our community and supports the project’s growth. The printing of the phrasebooks is often organized locally. Updating the tables is a time consuming task, so feedback from helpers is an important motivation. In the last month, we saw the demand shift to the south of Europe, where current policies have moved refugees out of sight without providing substantial support. The need for shelter and welcoming culture has not diminished, and language support is only a very small part of what is necessary.

What’s next for the Refugee Phrasebook? How do you see it evolving?

Though it might be easy to start projects like this it can be harder to sustain them. At the moment we are focussing on consolidating the project while expanding the target language base to improve on translations of prominent but lesser known African languages like Tigrinya.

The growing and changing data set has been included in various other projects from the beginning, often without us even knowing about it. The evening before Refugee Phrasebook received the Ars Electronica Award of Distinction in the category Digital Communities, we received an email that someone in Washington had used it in an app.

It lives forth in apps, language learning cards, other aid websites, etc. and is a great example for open data and peer to peer.

We do not see it growing and growing, but are looking to build it into a sustainable, stable resource that is easy to use, to expand and adapt into other projects. We hope to continue to develop the global community we have established through the phrasebook.

Posted 07 December 2016