Help us protect the commons. Make a tax deductible gift to fund our work. Donate today!

It is time to update our mental models about open knowledge

I like to say I am a “writer who lawyers”. I begin here because I want to name my biases up front. I am a lawyer, but I come to this work first and foremost as a writer thinking about the conditions that will allow us to continue to share knowledge publicly. And in spite of—or perhaps because of—the fact that I am a lawyer, I have a healthy skepticism about the power of legal terms and conditions. The law will play a role, but the challenge of keeping the internet human will ultimately be navigated by the stories we imagine and tell.

We need new stories.

I spent the first 15 years of my legal career working in intellectual property. For most of that time, I was part of the open movement, fighting overly restrictive intellectual property laws to promote access to knowledge. But over time, I began to feel like the message of open licensing did not resonate with me in the same way, especially in my identity as a writer. Eventually I left the open movement to go into the field of privacy.

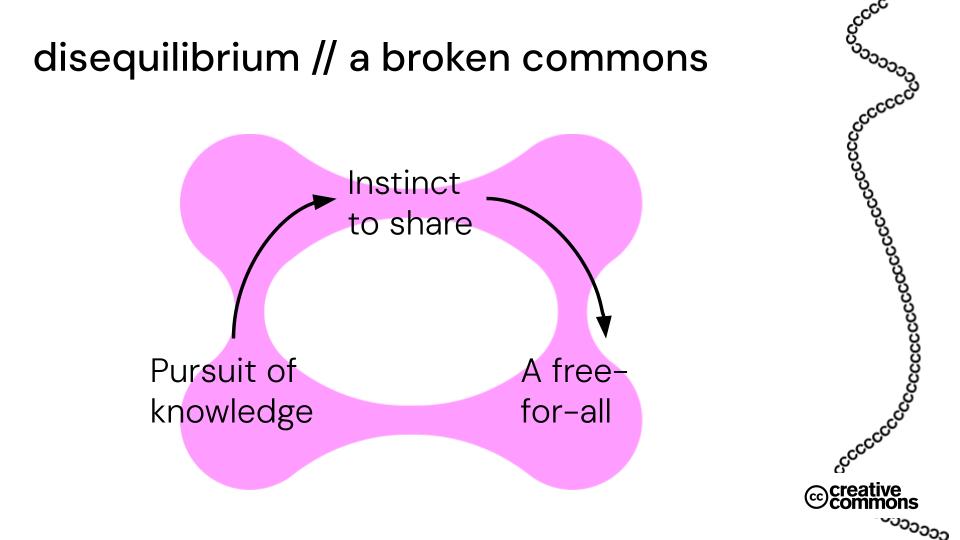

Immersing myself in digital privacy led me to realize why the story of open felt incomplete. We had been undervaluing the role of boundaries around reuse. The tension between the instinct to share and the need for boundaries around reuse is the point. And right now, that tension is completely out of balance. Instead, what exists online is a free-for-all.

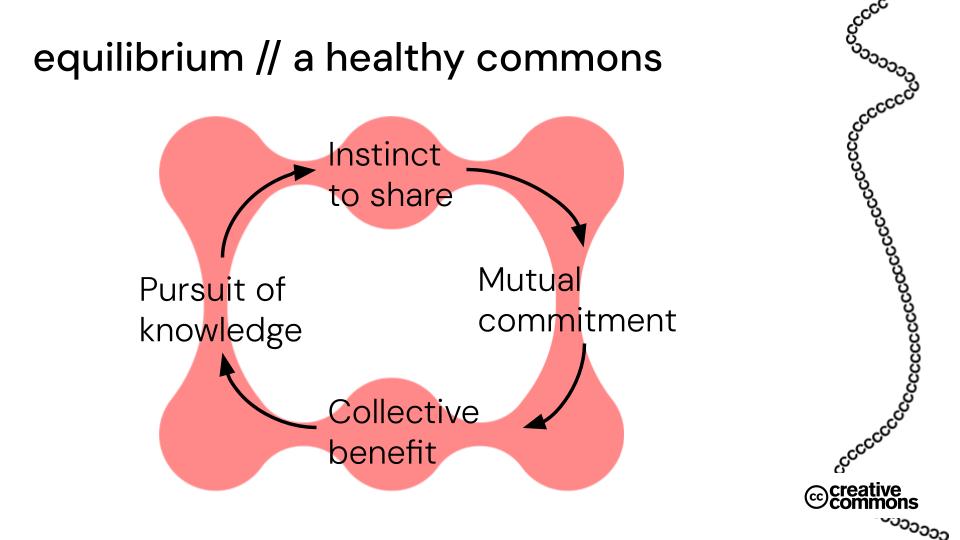

If you are familiar with the concept of a commons, you know it requires shared rules that govern reuse of resources. Those shared rules represent a mutual commitment by producers and reusers, and they ensure that the cycle leads to collective benefit and begins again. A free-for-all, on the other hand, has no shared rules. As a result, we are losing the instinct to share.

What happened to the commons?

It would be easy to blame AI for this situation, but it is not so straightforward. AI is simply speeding up and exacerbating longstanding challenges with open knowledge. As privacy scholar Daniel Solove has written, “AI is continuous with the data collection and use that has been going on throughout the digital age.”

In preparation for this talk, I went back and reread the brilliant CC Summit keynote “Open As In Dangerous” by Chris Bourg from 2018 and the seminal Paradox of Open report by the Open Future Foundation. For many years, these and countless other voices have been warning us about the vulnerabilities that open knowledge creates. Whether it is the use of CC-licensed photos for facial surveillance technology or the creation of Grokipedia, it is clear that open content is particularly vulnerable to abuse.

But of course, it is not just open content that is vulnerable. All content online today has essentially been treated as fair game. The free-for-all extends to everything online.

This has led to a vast renegotiation of what it means to share publicly, still currently underway. We see this in the massive wave of litigation against AI services, the rise of paywalls and commercial licensing deals, the introduction of new technologies to increase control over content in ways that scale back the open web, and the extreme backlash against AI by creators and the general public.

All of this constitutes a threat to open access to knowledge. It is unlikely that the incentives to share can outweigh all of the growing countervailing forces at play: economic, moral, safety, more. We cannot respond by accepting these risks and harms as inherent and inevitable costs of public sharing knowledge.

Changing our mental models

To meet the moment, we need to rethink our most fundamental assumptions about open knowledge.

The old taxonomies no longer apply.

For a very long time, we have used categories to help us determine the appropriate rules for sharing knowledge. Open content could be licensed one way, while open data had different parameters. This distinction no longer applies when everything online is used as data by machines. Even the difference between copyrighted material and public domain is not very useful, since even copyrighted works are largely used by machines for the public domain material within them (e.g., facts and ideas).

Copyright is not the main event.

The original “enemy” of the open movement was copyright, and things were simpler back then. Even the most restrictive open license was more permissive than the default under copyright law, so any boundaries we set around the commons were still fighting the copyright war. Overly restrictive copyright laws still cause problems today, but they are no longer the biggest threat against the commons. In fact, it is copyright’s weakness in the context of machine reuse that is the real challenge. The inapplicability of copyright in protecting against unwanted machine reuse guts the CC licenses of the same ability, creating the free-for-all even on CC-licensed content. And importantly, because the aim was to avoid having CC licenses impose restrictions on activity that was otherwise allowed under copyright, this was by design.

We have to stop confusing property with morality.

This is where I depart from my younger self and from many of my peers in the open movement. I think we have let important principles like the notion that facts and ideas should not be privately owned, or the fact that some permissionless reuse plays a critical role in free expression, convince us that the scope of copyright is an ethical line. The logic goes: if no one can own it, then no rules should apply. This leads to an impoverished sense of morality, where the only justification for constraint is property rights. As Robin Wall Kimmerer says, “In that property mindset, how we consume doesn’t really matter because it’s just stuff and the stuff all belongs to us. There is no moral constraint on consumption.”

The ethics of sharing—which is what open is about—needs to be broader than what we can own.

Boundaries benefit us all.

Boundaries on reuse are what create the reciprocity that fuels a commons. Without them, there is no assurance that sharing leads to collective benefit, and people lose their instinct to share. But boundaries can also have social value in their own right. Even when sharing in public, people rightfully expect some boundaries around how their works are used, regardless of what copyright law says. This is foundational in the field of privacy, but somehow we lose sight of it when we are sitting in the realm of content sharing. Daniel Solove writes: “People expect some degree of privacy in public, and such expectation is reasonable as well as important for freedom, democracy, and individual wellbeing.” Similarly, we establish boundaries around reuse of knowledge because those protections serve us all.

Open should not be a purity test.

The open movement has had incredible success creating global standards, and this has helped make it so successful. But the emphasis on standardization has led us to hyper-focus on definitions, and this focus is distracting us from the bigger picture. What matters is not open versus closed, or even abundance versus scarcity. We need to focus on values, not prescriptions. Open licensing has always been conditional, and it has always been a spectrum. This means we have to accept that there will be gray areas. What we lose in certainty, we will gain in relevance and moral clarity. As Rebecca Solnit says, “Categories are where thoughts go to die.”

Where do we go from here?

All of this leads back to where we began. We have to reconstruct the mutual commitment that keeps the commons cyclical.

Rebuilding the mutual commitment that comes with sharing knowledge requires us to balance opposing values. On the one hand, we must protect important freedoms of the reusing public. On the other, we must establish boundaries around responsible reuse. The goal is to be as open as possible and as restrictive as necessary. And before we start panicking about slippery slopes, we should remember there is an important limiting principle we can leverage: does the boundary shift power in ways that further concentrate it or redistribute it? We can also ask whether there are ways to mitigate a boundary’s effect on access.

We already have a good sense of the dimensions of boundaries around responsible reuse. They all have roots in the existing CC license suite.

Attribution: While the AI landscape complicates methods and norms for attribution, the principle is more important than ever for informational integrity, authors rights, and transparency.

Reciprocity: Molly Van Houweling calls this “extractability,” the idea that those extracting facts and ideas from others’ works have a moral responsibility to ensure that knowledge remains extractable by others. This is essentially about crafting a ShareAlike obligation for the age of AI.

Financial sustainability: This has been a longtime challenge in the open movement, and it is more urgent than ever. It is not about preserving business models, it is about financially sustaining the production of knowledge and culture as public goods.

Prohibitions on harmful use cases: This dimension may feel less familiar in open licensing, but the sentiment is one we hear regularly. There are simply some use cases or even actors that feel out of bounds for people sharing knowledge because of the harm they cause.

How do we catalyze a mutual commitment around prosocial boundaries in the current free-for-all environment? Open Future Foundation’s Paul Keller has written: “For any response to succeed in preserving a diverse and sustainable information ecosystem, collective action is required—both bottom-up, through coordinated action by information producers, and top-down, through political will to enable redistribution via fiscal interventions.” There is no single solution, and we need to tackle it from all directions.

For the bottom-up efforts, we can leverage the tools we have. Norms and social pressure have a role to play, though it is hard to put full faith in voluntary action right now. We can also explore methods for legal control, including both contract and copyright law. As Nilay Patel has said, “Copyright is the only functioning regulation on the internet,” which makes it impossible to avoid considering it as one lever to employ.1 Finally, there is the strategy of controlling access. This is the most uncomfortable tactic because of the collateral damage it risks, and it requires extreme care. But if AI companies will not pay attention voluntarily, technical controls around access look increasingly necessary.

There are many in the open movement already experimenting with these efforts, including the Mozilla Data Collective, the differentiated access model proposed by Europeana and the Open Future Foundation, the NOODL license, and many more. Creative Commons is also actively thinking about how to build a framework that re-instills mutual commitment into the ecosystem. Many of you have been following along as we experiment with an AI preference signals framework we’ve been calling CC signals. While the path we will take is evolving, the goal is the same. We need to come together to define and sustain the boundaries that serve us all.

I will end with the words of Ruha Benjamin: “We need to give the voice of the cynical, skeptical grouch that patrols the borders of our imagination a rest.”

We can imagine a better way.

1 While copyright law is ill-equipped to function as a method of control over machine reuse (and rightly so, considering the importance of not treating facts and ideas as private property), copyright law still has a role to play because of the uncertainty around its application on a global scale. Granting copyright permission in exchange for agreement to certain conditions could still be a valuable offer to some reusers.

Posted 12 February 2026