Looking forward and back: Five years at Creative Commons

This month, I’ll mark five years as CEO at Creative Commons. That makes me the longest-serving CEO in the organization’s history, and it’s also the longest I’ve served with the same job title. Every day I get to work with some of the brightest, most dedicated staff and community members in the open movement. Anniversaries are a good time to reflect, and as we all arrive home from our annual CC Summit in Lisbon, I wanted to share a few reflections on where we’ve come from, and where we’re headed.

TL;DR – In the last five years we’ve rebuilt CC from the ground up, with a more solid financial foundation; a revitalized multi-year strategy and plan to focus on a vibrant, usable commons powered by collaboration and gratitude; and a renewed and growing network. We’ve developed and launched new projects and programs like CC Search and the CC Certificate program, and through it all, played a vital role in defending, advancing, and stewarding the commons.

We produced this video, entitled “Remix,” not long after I started at CC to share our new strategy.

Some key facts. In the last five years, we’ve:

- Articulated a new vision for CC, with a 5-year strategy to bring it to life, that focuses on a “vibrant, usable commons, powered by collaboration and gratitude”

- Developed and launched CC Search, now indexing over 300M images, working closely with partners like the NY Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cleveland Museum, and Flickr

- Redesigned the entire Creative Commons Global Network from the ground up, from codes of conduct to community prioritization and collaboration, with a goal of being more open, accountable, and community-led. The new network is nearly 3x larger than the previous affiliate community.

- Established “The Big Open,” a platform to acknowledge the interconnected nature of the many communities we work in, including Mozillians, Wikipedians, Open Education, Open Science and academia, Open Government, and Open Data

- Co-created the CC Certificate with community experts and advisors, and certified over 250 people from all over the world to be practitioners and advocates

- Authored the State of the Commons report, published every year since 2015 to demonstrate the size and reach of the Commons online, today at over 1.4B works (with the next report out in mere days)

- Hosted the largest and broad-reaching community-led CC Summits ever, in Seoul, Toronto, Toronto (again), and Lisbon

- Raised over $26M from foundations, corporations, thousands of individual donors, and dedicated event sponsors, to support our work and community around the world

- Worked with institutions around the world to help expand and protect the commons, from the New York Met, to Flickr, to Medium, to MIT’s edX platform. In each case, we’ve been there to teach, advise, support, and advocate on behalf of CC users, open knowledge, and shared creativity

- Built a more diverse team at Creative Commons, with a majority of both leadership and staff who are women, and a global staff that better represent the communities and cultures we serve, and the geographies in which we work

The all-new CC Search

We’ve had some difficult moments too. In 2015, CC was forced to make a round of difficult layoffs in order to stabilize our budget and program. We recovered, but those kinds of changes are painful for everyone. In 2017, we learned that CC community member and friend Bassel Khartabil had been murdered by the regime in Syria. Many of us joined together with his family and friends to create a fellowship in his name, and I’m proud to see that Majd Al-Shahibi will speak at this year’s summit as the inaugural Bassel Khartabil Fellowship recipient.

This can be a lonely and unforgiving job. People treat you like a character — like the Office of the CEO — not like a person who has feelings, hopes, and doubts. And no doubt I have made mistakes. Like many in a role like this, I constantly replay how things worked out, and wonder how I might have done them differently in a different context. I think it’s normal for leaders to do that, and I’d worry about anyone who says they regret nothing, or would never change a past decision. Most of the leaders I admire obsess about doing the right thing, both before and after the fact, but also recognize that we almost always have to do something — hopefully the right thing, or at least the best thing for the moment we’re in, with the information we have. Still, within these difficult moments lies the knowledge that everything we do moves us towards a more equitable world.

None of this work would be possible without the team of talented humans who make up the CC team. I am full of gratitude for their daily energy, excellence, and commitment to the work we do. CC is also quite fortunate to have a strong Board of Directors who have provided mentorship, advice and counsel, and helpful criticism and support. I especially want to acknowledge our former board chair Paul Brest, whose board term ended last year, and who taught me a great deal about leadership, management, and strategic planning (and logic models). Finally, I want to thank my wife Kelsey, who was an active leader in the CC movement long before I came along, and who continues to support my work as an advisor and partner.

Creative Commons Global Summit by Sebastiaan ter Burg.

What’s next?

Creative Commons’ 20th anniversary is just around the corner (Jan 15, 2021), and it deserves a celebration worthy of the organization’s reach and impact. We’ve already started planning, and we hope to create a celebration that looks as far forward as it does back.

CC Search is taking off, and we’ll soon be adding more content types like open textbooks and audio. We’re also working on enhanced search tools that will enable new types of discovery and re-use.

The CC Certificate continues to grow and sell out with each cohort. We’ll be opening up a round of scholarships to improve accessibility for anyone who wants to take the course (though all the content is also CC BY, allowing anyone to read, copy, and remix it). We’re also expanding the content to serve additional communities, like the GLAM sector.

And this year, for the first time in CC’s history, the Global Network will lead and govern itself, set priorities and drive community growth and development. That’s a profound change, and a collaborative result that I’m certain will have an incredible impact.

There’s so much more to do, so many important ways we can help. “Pick big fights with your enemies, not small fights with your friends,” has been a favorite phrase of mine, and today there remain so many vital fights to have on behalf of shared knowledge and free culture. And CC has so many good friends to fight them with. I’m deeply grateful for those collaborations.

I look forward to doing this work for many years to come, with all of you in The Big Open.

Meet CC’s 2019 Google Summer of Code students

This year, CC is participating in Google Summer of Code (GSoC) as a mentoring organization after a six year break from the program. We are excited to be hosting five phenomenal students (representing three continents) who will be working on CC tech projects full-time over the summer. Here they are!

Ahmad Bilal

I am Ahmad Bilal, a Computer Science undergrad from UET Lahore, who likes computers, problems and using the former to solve the later. I am always excited about Open Source, and currently focused on Node.js, Serverless, GraphQL, Cloud, Gatsby.js with React.js and WordPress. I like organizing meetups, conferences and meeting new people. I view working in GSoC with Creative Commons, one of the biggest opportunities of my life. Cats are my weakness, and I am a sucker for well-engineered cars.

Ahmad will be taking ownership of the CC WordPress plugin, which simplifies the process of applying CC licenses to content created using the popular WordPress blogging platform. He will be updating it to use the latest WordPress best practices, resolving open issues, and adding new features like integrating with CC Search. Ahmad’s mentor is our Core Systems Manager Timid Robot Zehta, backed up by Hugo Solar.

You can follow the progress of this project through the GitHub repo or on the #cc-dev-wordpress channel on our Slack community.

Dhruv Bhanushali, credit: Arpit Gupta, CC BY

Dhruv Bhanushali

I am Dhruv Bhanushali, a Mumbai-based software developer recently graduated from IIT Roorkee. I started programming as a hobby some five years ago and, having found my calling, am now am pursuing a career in the field. I have worked on a lot of institute-level projects and am excited to expand the reach of my code to a global scale with CC through GSoC. Apart from development, I am a huge music fan and keep my curated collection of music with me at all times. I also love to binge watch TV shows and movies, especially indie art films.

Dhruv will be working on an original project, CC Vocabulary, which is a collection of UI components that make it easy to develop Creative Commons apps and services while ensuring a cohesive experience and appearance across CC projects. These components will be able to be used in sites built using modern JavaScript frameworks (specifically Vue.js) as well as simpler websites built using WordPress. CC’s Web Developer Hugo Solar serves as primary mentor, with backup from Sophine Clachar.

You can follow the progress of this project through the GitHub repo or on the #gsoc-cc-vocabulary channel on our Slack community.

María Belén Guaranda Cabezas, CC BY-NC-SA

María Belén Guaranda Cabezas

Hello! My name is María, and I am an undergraduate Computer Science student from ESPOL, in Ecuador. I have worked for the past 2 years as a research assistant. I have worked in projects including computer vision, the estimation of socio-economic indexes through CDRs analysis, and a machine learning model with sensors data. During my spare time, I like to watch animes and reading. I love sports! Specially soccer. I am also committed to environmental causes, and I am a huge fan of cats and dogs (I have 4 and 1 respectively).

María will be working on producing visualizations of the data associated with more than 300 million works we have indexed in the CC Catalog (which powers CC Search) and how that data is interconnected. These visualizations will enable users to understand how much CC-licensed content is available on the internet, which websites host the most content, which CC licenses are used the most, and much more. She will be mentored by our Data Engineer Sophine Clachar with backup from Breno Ferreira.

You can follow the progress of this project through the GitHub repo or on the #gsoc-cc-catalog-viz channel on our Slack community.

Ari Madian, credit: Ellen Madian, CC0

Ari Madian

I am an 18 year old, Seattle based, mostly self taught, Computer Science student. I originally started programming by tinkering with Python, and eventually moved into C# and the .NET framework, as well as JS and some web development. I like Chai and Rooibos teas, volunteering at my local food bank, and some occasional PC gaming, among other things. I’m now working with Creative Commons on Google Summer of Code!

Ari will be working on creating a modern human-centered version of our CC license chooser tool, which is long overdue for an update. His work will focus on design and usability as well as code. CC’s Front End Engineer Breno Ferreira is the primary mentor for this project with support from Alden Page.

You can follow the progress of this project through the GitHub repo or on the #gsoc-license-chooser channel on our Slack community.

Mayank Nader, credit: Rohit Motwani, CC BY

Mayank Nader

I am Mayank Nader, a sophomore Computer Science student from India. Currently, my main area of interest is Python scripting, JavaScript development, backend, and API development. I also like to experiment with bash scripting and ricing and configuring my Linux setup. Apart from that, I like listening to music and watching movies, documentaries, and tv shows. I am very much inspired by Open Source and try to contribute whenever I can.

Mayank will be working on building a cross-platform browser plugin that allows users to search CC-licensed works directly from the browser and enable reuse of those works by providing easy image attribution tools. Users will be able to find content to use without having to switch to a new website. Mayank will be mentored by CC’s Software Engineer Alden Page with support from Timid Robot Zehta.

You can follow the progress of this project through the GitHub repo or on the #gsoc-browser-ext channel on our Slack community.

You can visit the Creative Commons organization page on Google Summer of Code site to see longer descriptions of the projects. We welcome community input and feedback – you are the users of all these products and we’d love for you to be involved. So don’t hesitate to join the project Slack channel or talk to us on GitHub or our other community forums.

What does it mean to have a shared culture? A wrapup from this year’s CC Global Summit

Another year, another incredible Creative Commons Global Summit! This year, nearly 400 Creative Commoners gathered in Lisbon, Portugal to lift their voices in support of the Commons as advocates, activists, creators, and community members dedicated to a more open and sharing world.

It’s all about Community

The Global Summit was designed by the community, for the community to inspire action and events for this group of participants from around the world. Each one of the over 130 sessions was chosen by our volunteer program committee, proposed by CC chapters and organizations from around the world. From Portugal to Tanzania to New Zealand, our presenters came from hundreds of local contexts, sharing stories, data, projects, and ideas at the beautiful Museu do Oriente, our main venue.

At night, we welcomed participants to Capitolio, where we heard from five community keynotes and two invited keynotes. Diversity, equity, and inclusion were themes throughout – Natalia Mileczyk invoked a quote from Shirley Chisholm, “When they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”

Fortunately, there were chairs at many tables at the CC Summit.

“Now is the time for Genuine Change:” Global Summit Keynotes

Our five community keynotes came from three continents and a variety of disciplines. From Majd al-Shihabi’s work on decolonizing archives in Palestine to Sophie Bloeman’s Commons Network project, the five keynotes demonstrated their expertise and passion for the values of the Commons.

https://twitter.com/QUT_IP/status/1126765898398724099

https://twitter.com/dajbelshaw/status/1126567202294050816

Our invited keynotes, Adele Vrana and Siko Bouterse from “Whose Knowledge” and James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain spoke as well, with narratives of colonization, inclusivity on the open web, the public domain, and… comic books.

The Creative Commons Network

The Summit also marked the first meeting of the expanded Creative Commons Global Network, re-launched in 2016. The Global Network is three times larger than before and now comprises 37 chapters, 368 individual members, and 43 institutional members, many of whom attended this year’s Summit.

At this year’s Newbie Breakfast, dozens of new Summit attendees gathered on the first day of the Summit to create a welcoming space for new participants.

A nuanced view of “open”

What does it mean to be “open?” From questions of indigenous knowledge to CC business models to the implications of Artificial Intelligence, Summit participants asked the hard questions in nearly every session.

One particularly interesting panel focused on artists’ relationships to copyright, with a number of Portuguese artists discussing their work, including Summit graphic designer João Pombeiro. The panel featured a special guest appearance from Steve Kurtz of the Critical Art Ensemble via video call. They questioned the need for artists to exert strong power over their intellectual property and discussed the difficulties of making ethical art in 2019.

Copyright reform: What’s Next?

On the heels of the difficult loss in the European Union, much of the CC Summit was spent planning for the future of copyright around the globe. Many sessions, including a meeting of the copyright reform platform, touched on the challenges and opportunities confronting the movement in 2019 and beyond.

The CC community continued to explore ways to engage in productive copyright reform. We heard from experts from around the globe who shared their strategies and experiences in copyright law reform advocacy in the “How to Win the © Wars” session. CC allies also shared their work going on at WIPO, especially related to the agenda in support of expanding crucial limitations and exceptions to copyright for education, research, and libraries. Paul Keller from Communia shared lessons learned from the long and winding road of the EU copyright directive, and pushed for Creative Commons to actively contribute as the directive is implemented into the national laws of the member states over the next two years. And a diverse group of advocates met to lay out thematic areas and rough project plans for the copyright reform platform over the coming months.

Gratitude

Thank you to all presenters, volunteers, participants, and staff who made this event a success. We couldn’t have done it without you!

Thank you also to our sponsors Private Internet Access, MHz Foundation, Mozilla, Re:Create, Flickr, Lumen Learning, and UPTEC.

Get involved

We invite you to join us on Slack in the #cc-summit channel or social media @creativecommons to connect with the community, learn more about next year’s summit, or our work in search and discoverability, open access, open education, and more. View photos from the event by Sebastiaan ter Burg and Iñigo Sanchez on CC’s Flickr page.

Meet CC: The 2019 Creative Commons Global Summit Scholarships

Every year, Creative Commons invites community members from around the world to join us at our Global Summit. It is crucial that we come together as a community, celebrate each other, light up the commons, and collaborate. In order to reach the largest number of community members possible, we invest a significant amount of resources into our scholarship program, which this year supports 150 participants, or 38% of all Summit attendees. Summit scholarship recipients come from 59 countries and represent every world region. CC has invested more money and supported an increasing number of participants over the past few years, providing an average gift of over $600 to give $90,700 in total in 2019.

This year, we’re welcoming representatives from organizations including: Derechos Digitales, Global Voices, Kenya Copyright Board, Jordan Open Source Association, Aga Khan University, Jamlab, Visualizing Palestine, Communia, Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, ANSOL – Portuguese Association for Free Software, Karisma Foundation, SPARC Africa, and Open Culture Foundation. These professionals are experts in their fields and leaders in their communities. While the majority of our scholarship recipients come from Europe (39%), we have a relatively even spread of world regions represented, with 66% joining us from the Global South.

Below, hear from eleven scholarship recipients about their experience and background, their sessions, and what they are most looking forward to at the CC Global Summit.

Juliana Soto, CC Colombia

Juliana Soto, CC Colombia

I’m part of the CC community in Colombia since 2010 and I’m excited to participate in this year’s CC Global Summit. I’m involved with the free culture movement in my region because I believe in collaboration, openness, and diversity and because we need to keep saying that sharing is not a crime. I’m pleased to be a speaker in four sessions during the Summit and I definitely want to highlight one: “Common strategies in Latin America” an open conversation on Saturday, May 11 at 9 am.

Subhashish Panigrahi, CC India and Bangladesh

Subhashish Panigrahi, CC India and Bangladesh

I’m Subhashish, a documentary filmmaker and open culture activist by night and a community manager by day. Having been a part of the CC community since 2011, this is going to be my first summit and I cannot be more excited to meet in person many of mentors and old friends as well as make new friends. I am based in Bengaluru, India where I got involved with the Wikipedia/Wikimedia community and then with the CC and Openness community. I believe that knowledge only grows and spreads when shared in an open manner—CC revolutionizes the way knowledge is shared in society. On Saturday (May 11), I will be speaking about OpenSpeaks, a project that I founded to create open resources like OER, Open Toolkits, and Open Source software to help educate language archivists.

Emilio Velis, CC Salvador

Emilio Velis, CC Salvador

I’m Emilio and I am part of the El Salvador CC Chapter. I have been involved in my local chapter since 2013, and also been part of other communities related to technology and open hardware. I am eager to be part of this summit because I’m interested in how we can work together to document and share open projects in a way that people can get the best out of it. This time, I am presenting a session this Friday at 4pm on ontologies for open hardware and how different communities are working on it. I’m looking forward to seeing you all!

Siyanna Lilova, CC Bangladesh

Siyanna Lilova, CC Bangladesh

My name is Siyanna and I’m the Global Network Representative of the newly found CC Bulgaria Chapter. For the last year I’ve been actively involved with the copyright reform and developing the open knowledge movement in Sofia. I’m excited to attend my first Global Summit and I am eager to meet so many like minded people from around the world working together to create a more collaborative and open future.

Kin Ko, CC Hong Kong

I’m Kin Ko, a CC member from Hong Kong. Most of the time we are working with the Chinese community on open content and culture, and I’m excited to learn about the experiences from, and share our learnings with, other parts of the world.

I’ve been a user and adopter of CC because I believe in openness and diversity. In recent years I’ve taken a step forward to get involved in some volunteering works, such as joining the CC Global Summit program committee. I’m the founder of LikeCoin Foundation which is running Civic Liker, a movement to encourage people to nano tip open contents. Technically speaking, we are building LikeChain, a blockchain for open content registry. I’ll be hosting the session “Civic Liker – a movement to reward CC licensed contents with a monthly budget” on Saturday 11-11:45am. i’m easily reachable by @ckxpress – Telegram/Twitter/LINE/Messenger/WeChat and email kin@ckxpress.com

I’ve been a user and adopter of CC because I believe in openness and diversity. In recent years I’ve taken a step forward to get involved in some volunteering works, such as joining the CC Global Summit program committee. I’m the founder of LikeCoin Foundation which is running Civic Liker, a movement to encourage people to nano tip open contents. Technically speaking, we are building LikeChain, a blockchain for open content registry. I’ll be hosting the session “Civic Liker – a movement to reward CC licensed contents with a monthly budget” on Saturday 11-11:45am. i’m easily reachable by @ckxpress – Telegram/Twitter/LINE/Messenger/WeChat and email kin@ckxpress.com

Alexandros Nousias, CC Greece

Alexandros Nousias, CC Greece

It was back in 2007 when with no resources at all I took the plane to Dubrovnik to attend the CC Global Summit. Unofficially I had been following CC since 2004 but never as part of the community. That moment changed my life as I came across with people, ideas, trends, methods and tools that would define me as a professional, a citizen and an individual. I’m Alexandros Nousias, CC Greece Legal Lead and on Friday at the Building the Commons Lightning Talks (4:30pm – 5:30pm), I will explain why after a 15 year discussion around the topic, we need to re-engineer the concept of open as it applies in a) digital creation b) you and me as data subjects and information agents, taking into account the technological advancements of now.

Mehtab Khan, Creative Commons

Mehtab Khan, Creative Commons

I’m Mehtab, a doctoral candidate at University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, and a former Research Fellow at Creative Commons. I’m from Pakistan and coming to the Global Summit from San Francisco, USA. I’m excited to attend because this is the first time I’ll be attending the Global Summit. I’m looking forward to participating in discussions about critical issues in the Open Movement and meeting community members from all over the world! I’m involved with CC because I believe that knowledge should be accessible and affordable for everyone. I’ll be a part of two sessions on May 9: “Do you use OpenGLAM? Help review shared #OpenGLAM principles” at 9:00 am, and “Traditional Knowledge and the Commons: What’s Next?” at 10:45 am.

Kamel Belhamel, CC Algeria

Kamel Belhamel, CC Algeria

I’m Kamel, coming from Algeria, I’m member of the Membership Committee of the Creative Commons Global Network Council. I’m excited to attend CC Global Summit 2019 – Lisbon, Portugal. I’ll be a part of a session on Open Access Scholarly Publication in Algeria. Also, I’ll attend Opening Africa , this collaborating session by CC Africa Chapters and individuals, which will highlight various achievements and developing inter-regional links for collaboration across Africa.

Nour El Houda, CC Algeria

Nour El Houda, CC Algeria

I’m Nour El Houda, coming from Algeria, I’m a member of CC Algeria Chapter. I’m excited to attend CC Global Summit 2019 – Lisbon, Portugal. I’ll be a part of a session on Ethics of Openness Lightning Talks on Thursday, May 9 from 11:00am – 11:25am.

Paula Eskett, CC New Zealand

Paula Eskett, CC New Zealand

Kia ora, I’m Paula from Christchurch, New Zealand. This year will be my 3rd CC Summit. I’m really excited because I’m in a new role within libraries in NZ (managing a district of public libraries) with a large team and have real opportunities and mandate to introduce and guide others in to our world of Open and CC. I’m looking forward to reconnecting with old friends, and making new connections and learning. I’ll be running a session on Day 1 at 1pm: Stories and SDG’s from the libraries of Aotearoa NZ. I’m the current president of our national library association LIANZA, and proud to share the way our libraries are a national force for equity, openess,community building and helping to bring to life the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) of the UN2030 agenda across New Zealand.

Veethika Mishra, CC India

Veethika Mishra, CC India

I’m Veethika Mishra, and I attended CC Global Summit the previous year (in Toronto) to propagate the idea of Openness in Design. After interacting with the amazing set of people at the conference, and learning about their passion and approach to make the world a better place, I decided to contribute to the movement actively. I’m from Bangalore, the Silicon Valley of India, and I work as an Interaction Designer.

CC Search is out of beta with 300M images and easier attribution

Today CC Search comes out of beta, with over 300 million images indexed from multiple collections, a major redesign, and faster, more relevant search. It’s the result of a huge amount of work from the engineering team at Creative Commons and our community of volunteer developers.

CC Search searches images across 19 collections pulled from open APIs and the Common Crawl dataset, including cultural works from museums (the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cleveland Museum of Art), graphic designs and art works (Behance, DeviantArt), photos from Flickr, and an initial set of CC0 3D designs from Thingiverse.

Aesthetically, you’ll see some key changes — a cleaner home page, better navigation and filters, design alignment with creativecommons.org, streamlined attribution options, and clear channels for providing feedback on both the overall function of the site and on specific image reuses. It’s also now linked directly from the Creative Commons homepage as the default method to search for CC-licensed works, and replaces the old search portal (though that tool is still online here).

Under the hood, we improved search loading times and search phrase relevance, implemented analytics to better understand when and how the tools are used, and fixed many critical bugs our community helped us to identify.

What’s next

We will continue to grow the number of images in our catalog, prioritizing key image collections such as Europeana and Wikimedia Commons. We also plan to index additional types of CC-licensed works, such as open textbooks and audio, later this year. While our ultimate goal remains the same (to provide access to all 1.4 billion works in the commons), we are initially focused on images that creators desire to reuse in meaningful ways, learning about how these images are reused in the wild, and incorporating that learning back into CC Search.

Feature-wise, we have specific deliverables for this quarter listed in our roadmap, which includes advanced filters on the home page, the ability to browse collections without entering search terms, and improved accessibility and UX on mobile. In addition, we expect some work related to CC Search will be done by our Google Summer of Code students starting in May.

We’re also presenting the “State of CC Search” at the CC Global Summit next month in Lisbon, Portugal, where we’ll host a global community discussion around desired features and collections for CC Search.

Get involved

Your feedback is valuable, and we invite you to let us know what you would like to see improved. You can also join the #cc-usability channel on CC Slack to keep up with new releases.

All of our code, including the code behind CC Search, is open source (CC Search, CC Catalog API, CC Catalog) and we welcome community contribution. If you know how to code, we invite you to join the growing CC developer community.

Thank you

CC Search is also made possible by a number of institutional and individual supporters and donors. Specifically, we would like to thank Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, Mozilla, and the Brin Wojcicki Foundation for their support.

Congratulations to the new 62 CC Certificate Graduates and 7 Facilitators!

From January to April 2019, Creative Commons hosted three CC Certificate courses and a Facilitators course to train the next cohort of Certificate instructors. Participants from Australia, Qatar, South Africa, Egypt, Indonesia, Canada, Argentina, United Kingdom, Colombia, Spain, Mexico, Denmark, New Zealand, Sweden, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and United States engaged in rigorous readings, assignments, discussions and quizzes. See examples of the participants’ assignments they’ve publicly shared under CC licenses. With these courses now complete, we are thrilled to announce 62 new CC Certificate graduates and 7 new CC Certificate facilitators!

Interested in taking the CC Certificate? We are now accepting new registrations for our June and September courses.

The CC Certificate provides an in-depth study of Creative Commons licenses and open practices, uniquely developing participants’ open licensing proficiency and understanding of the broader context for open advocacy. The training content targets copyright law, CC legal tools, as well as the values and good practices of working in the global, shared commons.

The CC Certificate is currently offered as a 10-week online course to educators and academic librarians. In late 2019 / 2020, Creative Commons will expand Certificate offerings to include 1-week boot camps, additional facilitator trainings, scholarships, and translations of the Certificate into multiple languages.

Congratulations to our 62 new Certificate and 7 facilitator graduates; we are filled with gratitude for their amazing work. Now… let’s go change the world!

Unleashing a Community in Action: this year’s CC Global Summit Keynotes

This year, we’re taking an alternative, community-centered approach to keynotes for the Creative Commons Global Summit. In addition to two keynotes from four esteemed colleagues in open knowledge and the public domain, we’re bringing six community leaders to the stage for short talks on their work and experience. They were identified and selected by the Summit program committee.

The Community Keynotes join us from four continents and a variety of disciplines. From technology to journalism, these Creative Commons Global Network members are accomplished leaders in their fields participating in crucial work for a more open world. These keynotes will be: Majd al Shihabi of Lebanon, Sophie Bloemen of Amsterdam and Brussels, Kelsey Merkley of Canada, Natalia Mileszyk of Poland, Dr. Haggen So of Hong Kong, and Ọmọ Yoòbá of Nigeria. Their bios can be found below.

Majd Al-Shihabi is a systems design engineer based in Beirut, applying systems thinking to as many fields as he can reach. He works with a wide range of academic and cultural institutions and archives in the region to build openness into their information systems. He is interested in knowledge production outside of traditional institutions and knowledge dissemination to wider audiences. Majd is interested in studying how urban environments evolve and are shaped, which he is studying at the American University of Beirut. He is the inaugural recipient of the Bassel Khartabil Free Culture Fellowship, where he worked on two projects: PalestineOpenMaps.org, running mapathons to vectorize the content of historic maps of pre-Nakba Palestine; and MASRAD:platform, an open source tool for archiving oral history collections.

Sophie Bloemen is Director and co- founder of Commons Network, a think tank and civil society initiative based in Amsterdam & Brussels. She writes and speaks on social-ecological transitions, the commons and new narratives for Europe. She is engaged in a number of projects and political processes that explore new, creative institutions, collaborative models and bringing the commons perspective to policy. She has worked as an advocate and public interest consultant on policy issues like health, trade, innovation and R&D. @sbloemen

Kelsey Merkley is the founder of UnCommon Women, a project designed to advocate for leadership roles for women and celebrate those in leadership through the UnCommon Women Colouring Book. She is an advocate with almost a decade of experience working with local, national, and global organizations. Previously she was Creative Commons Public Lead in South Africa and later in Canada where launched numerous community-building projects. Kelsey now lives and works in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Natalia Mileszyk is a lawyer and public policy expert dealing with digital rights, copyright reform and openness. She works for Centrum Cyfrowe, a leading Polish think-and-do-tank, where she analyses and comments on the social aspects of technology and a need for human-centered digital policy. She is also active in Communia Association for Public Domain and Creative Commons Poland. For the last three years, she has been actively involved in copyright reform advocacy at the European level. A graduate of the University of Warsaw and the Central European University in Budapest (LL.M.). You can find her on Twitter at @nmileszyk.

Natalia Mileszyk is a lawyer and public policy expert dealing with digital rights, copyright reform and openness. She works for Centrum Cyfrowe, a leading Polish think-and-do-tank, where she analyses and comments on the social aspects of technology and a need for human-centered digital policy. She is also active in Communia Association for Public Domain and Creative Commons Poland. For the last three years, she has been actively involved in copyright reform advocacy at the European level. A graduate of the University of Warsaw and the Central European University in Budapest (LL.M.). You can find her on Twitter at @nmileszyk.

Dr. Haggen So is the president of the Hong Kong Creative Open Technology Association and the public lead of Creative Commons Hong Kong. He is a visiting lecturer of the Hong Kong Community College and previously taught in Hong Kong Baptist University as lecturer in the department of Computer Science. Dr. So also has experiences in commercial software development and developed software products for renowned companies such as Kodak.

Dr. Haggen So is the president of the Hong Kong Creative Open Technology Association and the public lead of Creative Commons Hong Kong. He is a visiting lecturer of the Hong Kong Community College and previously taught in Hong Kong Baptist University as lecturer in the department of Computer Science. Dr. So also has experiences in commercial software development and developed software products for renowned companies such as Kodak.

Ọmọ Yoòbá is a journalist with eleven years professional experience in the Nigerian broadcast media. He has dedicated eight years of his lifetime to the propagation of the Yorùbá ecological knowledge and cultural on the digital space. As an advocate of multilingualism and internet universality, Yoòbá had worked with stakeholders in the effort to bridge the digital divide, giving minority languages a voice on the Internet of Things, and marginalised society access to digital resources. In addition to teaching the Yorùbá language on tribalingua.com, Yoòbá is a volunteer translator and has worked with Localization Lab to localize digital security and Internet circumvention tools (EFF). He is the Lingua Manager of Global Voices in Yorùbá. In 2018, he collated more than a hundred oral literature of the Yorùbá which is in the archive of the Firebird Foundation for Anthropological Research in Phillips, Maine, United States.

In addition to these community keynotes, CC has invited two keynotes from four international leaders in free culture and open knowledge. Our first invited keynote is Adele Vrana and Siko Bouterse, co-directors of Whose Knowledge?, a global campaign working to create, collect and curate knowledge from and with marginalized communities, so that the internet we build and defend is ultimately an internet for all.

Our second invited keynote is James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain, whose keynote will discuss music copyright, the Public Domain, and their work as advocates and lawyers to improve access to knowledge. Jenkins and Boyle recently spoke at our “Re-opening of the Public Domain” event in San Francisco. Watch the video to get a preview of their talk and read an interview with them on the CC blog.

The CC Global Summit will take place from May 9-11 in Lisbon. The program and registration is available at this link.

European Commission adopts CC BY and CC0 for sharing information

Last week the European Commission announced it has adopted CC BY 4.0 and CC0 to share published documents, including photos, videos, reports, peer-reviewed studies, and data. The Commission joins other public institutions around the world that use standard, legally interoperable tools like Creative Commons licenses and public domain tools to share a wide range of content they produce. The decision to use CC aims to increase the legal interoperability and ease of reuse of its own materials.

In addition to the use of CC BY, the Commission will also adopt the CC0 Public Domain Dedication to publish works directly in the global public domain, particularly for “raw data resulting from instrument readings, bibliographic data and other metadata.”

The European Commission joins governments such as New Zealand and the Netherlands in using CC licenses and CC0 to share digital resources it creates. Intergovernmental organisations, philanthropic charities, and funding policies already require CC licenses to be applied to the digital outputs of grant funds — to promote reuse of materials in the public good with minimal restrictions.

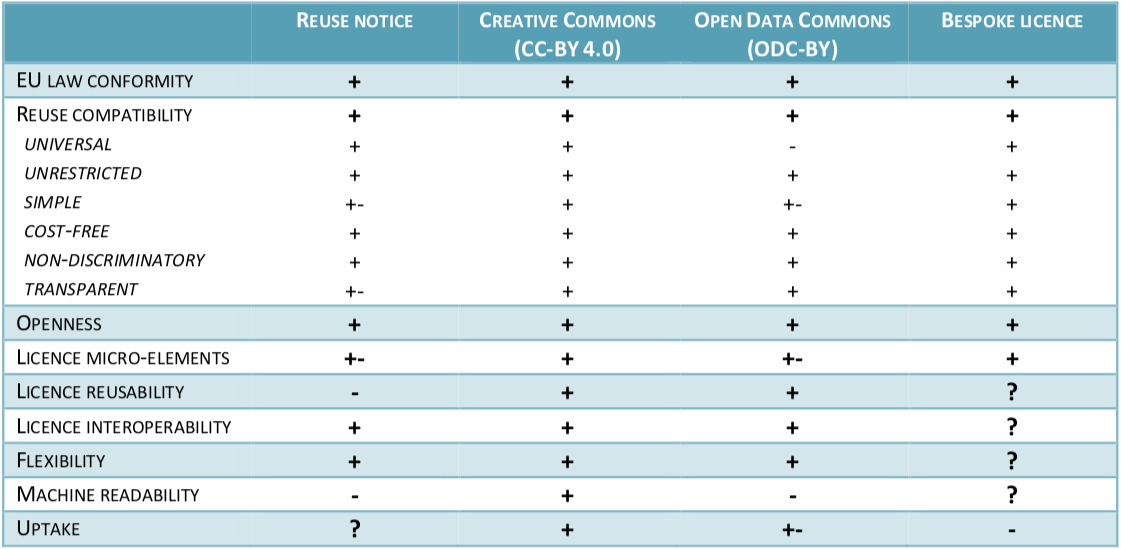

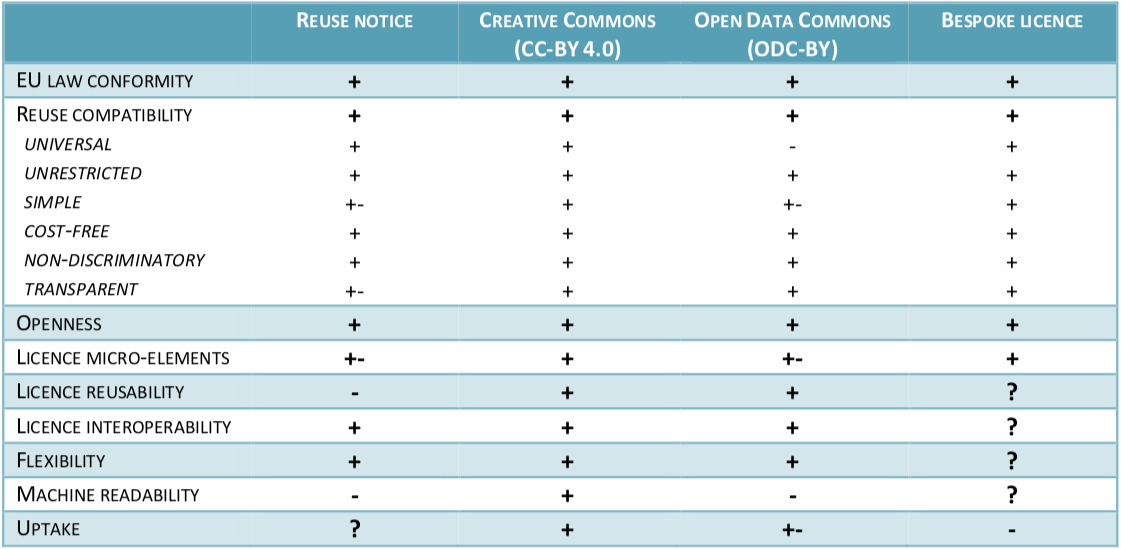

The decision to require reuse of Commission documents under CC BY and CC0 was determined alongside a study on available reuse implementing instruments and licensing considerations. Until now the Commission had been relying on “reuse notices” (a simple copyright notice with link to the reuse decision) that would accompany covered materials, but this practice produced “unnecessary administrative burdens for reusers and the Commission services alike.”

In 2014 the Commission released a recommendation on using Creative Commons licenses such as CC BY and CC0 Public Domain Dedication in the context of Member States sharing public sector information.

CC BY 4.0 receives top score in license evaluation

The study mentioned above evaluates various options for the Commission to consider for its own documents, including the “reuse notice”, CC licenses, the Open Data Commons licenses, and a potential bespoke Commission licence. Its authors determined that CC BY 4.0 is the license best aligned with the Commission’s principles for reuse. According to the report, CC BY 4.0 is:

- Universal: it is conceived to be applicable to all documents (at the choice of the licensor);

- Unrestricted: generally speaking, the only condition is attribution;

- Simple: there is no need for an application and it is user-friendly;

- Cost-free: the text of CC-BY does not require payment of fees;

- Non-discriminatory: terms of CC-BY are open to all potential actors in the market; [and]

- Transparent: the text of the licence is publicly available, accompanied by supporting documents, guidelines and other material in multiple languages.

The study notes that not all of the CC licenses and CC0 have been translated into the two dozen official EU languages; there are 10 remaining translations for CC 4.0 (some in progress) and 12 for CC0. We are working with the Commission and the CC EU network to complete the remaining translations.

Amid the disappointment with the vote in the Parliament on the copyright Directive last week, which leans toward a more restricted, less open web, it is heartening to see the Commission make progress on supporting reuse of the digital materials it creates and shares. We also look forward to upcoming vote this week on the recast of the Public Sector Information (PSI) Directive. This vote could increase the availability of PSI by bringing new types of publicly funded data into the scope of the directive, and provide improved guidance on open licensing, acceptable formats, and rules on charging.

The freedom to listen: Rute Correia on the power of community radio

Academic, producer, and open culture enthusiast, Rute Correia is a Lisbon-based doctoral candidate who produces the White Market Podcast, which focuses on free culture and CC music. As both a student of radio and producer herself, she is deeply connected to the Netlabel and CC music communities, utilizing her significant talents to showcase free music, culture, and Creative Commons through community radio and open source.

Academic, producer, and open culture enthusiast, Rute Correia is a Lisbon-based doctoral candidate who produces the White Market Podcast, which focuses on free culture and CC music. As both a student of radio and producer herself, she is deeply connected to the Netlabel and CC music communities, utilizing her significant talents to showcase free music, culture, and Creative Commons through community radio and open source.

Rute will be joining us at the Creative Commons Global Summit in Lisbon from May 7-9 to talk about her exciting new project, the Open Music Network. Find out more about the Summit, and don’t forget to register soon!

How did you become involved with and interested in open culture and music production? How would you encourage others to get involved?

It all started about 12 years ago. I joined Radio Zero, a student radio station in Lisbon, and they had a very open source-oriented ethos. That’s where I first found out about Creative Commons and, luckily, at that time there were lots of independent music labels in Portugal releasing music under CC. One thing led to another and I ended up doing a show only dedicated to music that was freely (as in beers!) available. It was the precursor of White Market Podcast, my show about CC-licensed music and open culture. What I find really exciting about open music is that there’s so much to discover and everything is accessible. Cultural industries tend to remain heavily closed, reinforcing the idea that culture is a privilege, but CC licenses challenge that and allow you to share your stuff with whoever you want. If you like music, I’d say the best way to start is to dive into larger pools of free music, like Starfrosch, Dogmazic, ccMixter, and Auboutdufil.

What is the role of radio in open source music production? Why is radio art important in the digital age?

Radio is the medium with the widest reach in the world – the International Telecommunication Union estimates that it reaches “95% of virtually every segment of the population” around the the world. As such, it is still a great tool for promoting music regardless of genre, and reaching out to newer audiences. But the connection can grow a lot deeper than that; for non-for-profit stations, open music can also be a valuable resource as it is shared with fewer restrictions than copyrighted music. For instance, stations using CC BY-SA songs can share that share the content they produce under the same license allowing their listeners to engage with their content beyond the broadcast schedule.

How do you “live open” in a closed source world? What open values do you bring to your work in academia and radio?

It can be hard sometimes. Sadly, I don’t think we’re at a stage where you can live fully “open”. We’re all limited by the reality around us: jobs, what friends and family do, etc. I try to keep things as open as possible: creating open processes and using free software is a good start in our daily lives. In academia, I try to follow guidelines regarding open science: using open formats and sharing data whenever possible. Beyond using and sharing only free content, I have tried to set up a collaborative workflow using Github to create content for White Market Podcast. It’s still a work in progress, though.

What are you going to be working on or presenting at the CC Summit?

Darksunn and I will be presenting the recently-formed Open Music Network – a non-profit organization focused on promotion, education and advocacy for the benefits of open music for both professional and personal use. The network links different actors in the open music community – such as platforms, labels, podcasts and radios shows, and even a venue.

What aspect of the CC Summit are you most excited about? What are you most looking forward to?

Just to take part in it is already crazy exciting for me! It’s going to be my first ever CC Summit and it’s a lovely coincidence that it’s taking place right at home. I look forward to welcoming other CC-lovers into Lisbon, as well as learning from their experiences with Creative Commons and in open culture.

A Dark Day for the Web: EU Parliament Approves Damaging Copyright Rules

Today in Strasbourg, the European Parliament voted 348-274 (with 36 abstentions) to approve the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. It retains Article 13, the harmful provision that will require nearly all for-profit web platforms to get a license for every user upload or otherwise install content filters and censor content, lest they be held liable for infringement. Article 11 also passed, which would force news aggregators to pay publishers for sharing snippets of their stories.

There was a potential opportunity to vote on amendments that would have removed the most problematic provisions in the draft directive, particularly Articles 13 and 11, but the preliminary vote even to consider amendments fell short by five votes, thus pushing the Parliament to move ahead and simply approve the entire package.

MEP Julia Reda called the decision “a dark day for internet freedom.” We agree. There was a massive outpouring of protest against the dangers of Article 13 to competition, creativity, and freedom of expression. This included 5+ million petition signatures, a gigantic action of emails and calls to MEPs, 170,000 people demonstrating in the in the streets, large websites and communities going dark, warnings from academics, consumer groups, startups and businesses, internet luminaries, and the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression. Even so, it was not enough to convince the European legislator to change course on this complex and damaging provision that will turn the web upside down.

Creative Commons CEO Ryan Merkley responded to the vote:

Despite an incredible show of public opposition to the directive, and an abundance of evidence that the proposals will favour large rights holders, damage online communities, slow or even stop innovation, and entrench established big tech players, the European legislature has decided to approve it. Regardless of this outcome, we’ll continue to work with Member States wherever we can to ensure the implementations of this directive minimize the negative impact we anticipate for the commons, and on users who want to share creativity and knowledge online.

We’re disappointed with the decision to push through Article 13 and 11, but the directive is not a total wash. There are some productive changes that will improve the situation of the commons, libraries & cultural heritage, and research sectors. For example, the directive includes a provision to ensure that digital reproductions of public domain works don’t get a separate copyright and will also be in the public domain. It includes text to improve the ability for cultural heritage institutions to preserve works and to make available copyrighted works from their collections that are no longer commercially available. And the directive slightly improves the copyright exception on text and data mining (TDM) by making mandatory an earlier optional provision that would expand the possibilities for those wishing to conduct TDM.

The final outcome of the European copyright directive reflects a disturbing path toward increasing control of the web to benefit only powerful rights holders at the expense of the rights of users and the public interest. It has been — and will continue to be — up to us all to fight for an open internet that sustains new creativity and upholds freedom of expression in the digital environment.

Juliana Soto, CC Colombia

Juliana Soto, CC Colombia Subhashish Panigrahi, CC India and Bangladesh

Subhashish Panigrahi, CC India and Bangladesh Emilio Velis, CC Salvador

Emilio Velis, CC Salvador Siyanna Lilova, CC Bangladesh

Siyanna Lilova, CC Bangladesh I’ve been a user and adopter of CC because I believe in openness and diversity. In recent years I’ve taken a step forward to get involved in some volunteering works, such as joining the CC Global Summit program committee. I’m the founder of LikeCoin Foundation which is running Civic Liker, a movement to encourage people to nano tip open contents. Technically speaking, we are building LikeChain, a blockchain for open content registry. I’ll be hosting the session “Civic Liker – a movement to reward CC licensed contents with a monthly budget” on Saturday 11-11:45am. i’m easily reachable by @ckxpress – Telegram/Twitter/LINE/Messenger/WeChat and email

I’ve been a user and adopter of CC because I believe in openness and diversity. In recent years I’ve taken a step forward to get involved in some volunteering works, such as joining the CC Global Summit program committee. I’m the founder of LikeCoin Foundation which is running Civic Liker, a movement to encourage people to nano tip open contents. Technically speaking, we are building LikeChain, a blockchain for open content registry. I’ll be hosting the session “Civic Liker – a movement to reward CC licensed contents with a monthly budget” on Saturday 11-11:45am. i’m easily reachable by @ckxpress – Telegram/Twitter/LINE/Messenger/WeChat and email  Alexandros Nousias, CC Greece

Alexandros Nousias, CC Greece Mehtab Khan, Creative Commons

Mehtab Khan, Creative Commons Kamel Belhamel, CC Algeria

Kamel Belhamel, CC Algeria Nour El Houda, CC Algeria

Nour El Houda, CC Algeria Paula Eskett, CC New Zealand

Paula Eskett, CC New Zealand Veethika Mishra, CC India

Veethika Mishra, CC India

Natalia Mileszyk is a lawyer and public policy expert dealing with digital rights, copyright reform and openness. She works for Centrum Cyfrowe, a leading Polish think-and-do-tank, where she analyses and comments on the social aspects of technology and a need for human-centered digital policy. She is also active in Communia Association for Public Domain and Creative Commons Poland. For the last three years, she has been actively involved in copyright reform advocacy at the European level. A graduate of the University of Warsaw and the Central European University in Budapest (LL.M.). You can find her on Twitter at @nmileszyk.

Natalia Mileszyk is a lawyer and public policy expert dealing with digital rights, copyright reform and openness. She works for Centrum Cyfrowe, a leading Polish think-and-do-tank, where she analyses and comments on the social aspects of technology and a need for human-centered digital policy. She is also active in Communia Association for Public Domain and Creative Commons Poland. For the last three years, she has been actively involved in copyright reform advocacy at the European level. A graduate of the University of Warsaw and the Central European University in Budapest (LL.M.). You can find her on Twitter at @nmileszyk. Dr. Haggen So is the president of the Hong Kong Creative Open Technology Association and the public lead of Creative Commons Hong Kong. He is a visiting lecturer of the Hong Kong Community College and previously taught in Hong Kong Baptist University as lecturer in the department of Computer Science. Dr. So also has experiences in commercial software development and developed software products for renowned companies such as Kodak.

Dr. Haggen So is the president of the Hong Kong Creative Open Technology Association and the public lead of Creative Commons Hong Kong. He is a visiting lecturer of the Hong Kong Community College and previously taught in Hong Kong Baptist University as lecturer in the department of Computer Science. Dr. So also has experiences in commercial software development and developed software products for renowned companies such as Kodak.

Academic, producer, and open culture enthusiast,

Academic, producer, and open culture enthusiast,