Help us protect the commons. Make a tax deductible gift to fund our work. Donate today!

Caroline Woolard, Capitoline Wolves, rendering of work in progress, 2016. Courtesy of the artist. Rendering, CC-BY-ND 4.0

The interdisciplinary artist Caroline Woolard engages with political economy and activism through radically innovative collaborative projects. Through “existing commoning projects like gifting, lending, borrowing, and sharing of land, labor, and capital,” Woolard’s work confronts the economic precarity of the present moment through a variety of media.

Caroline Woolard, Lika Volkova, Helen Lee, and Alexander Rosenberg, Carried on Both Sides, work in progress, 2016. Photo by Levi Mandel, CC-BY-ND 4.0

As a “cultural producer whose interdisciplinary work facilitates social imagination at the intersection of art, urbanism, and political economy,” Woolard’s work is collaborative, confrontational, and cooperative, drawing on a variety of experiences and voices.

Woolard’s newest work, “Of Supply Chains,” will be released this month on the project’s website.

How do you understand “the commons”?

I define “the commons” as shared resources that are managed by and for the people who use those resources. Creative Commons does an excellent job of bringing the Free Culture Movement to everyday life, as image rights are now understood in relationship to the commons. That said, I believe Silvia Federici when she writes that most things we call “commons” today are in fact “transitional commons” because in a true commons, the collective management of resources would be respected by, and even surpass, state and federal law.

Can you discuss the use of political economies in your work and how it relates to the concept of the commons?

Caroline Woolard, Barricade to Bed, 2013. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Ryan Tempro, CC-BY-ND 4.0

If “the commons” refers to the ways in which people share and manage resources together, then the commons is always a political, and economic, concept. Historically, the commons have been enclosed upon by state governance and by privatization. Today, the commons are enclosed upon by neoliberalism, what cultural theorist Leigh Claire La Berge describes as “the private capture of public wealth”. It is my hope that my art and design work can support existing commoning practices like the gifting, lending, borrowing, and sharing of land, labor, and capital. While artists who represent commoning in paintings or photographs might provide necessary space for reflection about the commons, in my work I employ one of two strategies: 1) co-creating living spaces for commoning, or 2) making objects and artworks for existing commons-based organizations. In other words, I try to support the commons, rather than represent the commons.

Because I aim to communicate across social spheres, I make multi-year, research-based, site-specific projects that circulate in contemporary art institutions as well as in urban development, critical design, and social entrepreneurship settings. Though I am often cited as a socially engaged artist, I consider myself to be a cultural producer whose interdisciplinary work facilitates social imagination at the intersection of art, urbanism, and political economy.

Caroline Woolard, Lika Volkova, Helen Lee, and Alexander Rosenberg, Carried on Both Sides, work in progress, 2016. Photo by Levi Mandel, CC-BY-ND 4.0

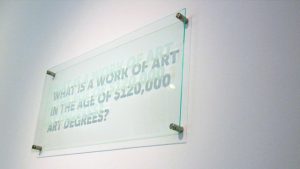

I create installations and social spaces for encounters with fantasies of cooperation. Police barricades become beds. Money is erased in public. A clock ticks for ninety-nine years. Public seats attach to stop sign posts. Cafe visitors use local currency. Office ceilings hold covert messages. Ten thousand students attend classes by paying teachers with barter items. Statements about arts graduates are read on museum plaques. My work is research-based and site-specific. I alter objects to call forth new norms, roles, and rules. A street corner, a community space, a museum, an office, or a school become sites for collective reimagining.

To make this shift from object to group, I concern myself with duration and political economy. When I source materials, invite joint-work, share or deny decision-making power, and shape future markets for each work, a community of practice emerges. Experience becomes a criterion of knowledge.

To the conventional labels of Title, Author(s), Materials, Dimensions, Date, and Provenance, I add Duration, forms of Property, Labor, Transactions, Enterprise, and Finance. Objects become materializations of collective debate; entry points for encounters with fantasies of cooperation.

Caroline Woolard / BFAMFAPhD, Statements, 2013. Courtesy of BFAMFAPhD / Caroline Woolard, photo CC-BY-ND 4.0

The objects I make cannot be disentangled from their economic and social lives. My Work Dress is available for barter only. My Statements increase in price according to student loan rates. Artists Report Back is made by BFAMFAPhD, a group that accepts community contributions. I understand art as mode of inquiry that expands beyond exhibition and toward life cycle; from display to production, consumption, and surplus allocation. I begin each project with an invitation. I facilitate an experience. A group gathers. I share and develop leadership. The project becomes a group effort, and the objects multiply. The objects are known in the group and shown much later.

You often work collaboratively with other artists. Do you see collaboration as essential to your process? How did you come to that conclusion?

Caroline Woolard, Work Dress, 2014. Photo by Martyna Szczesna, CC-BY-ND 4.0

I often work collaboratively because it allows me to refine my ideas in debate and in encounters with difference – difference of experience, of perspective, of values. I believe that a diversity of opinions strengthens projects because collaborators are challenged to confront their individual assumptions and either come to agreement as a group or make space to consent to individual expression or dissensus.

In collaboration, we often take time to speak about our individual and collective approaches to allocating time and money in projects. As collaborators attempt to agree upon which resources to share, collaboration becomes a conversation about political economy. We often ask: Which resources – time, money, space – are most important to us right now? How will we share the resources we accumulate together? Who has more time, space, or money in the group, and which institutions uphold this reality? By practicing shared work and shared decision making in a collaborative project, an economy of shared time and resources emerges. Practitioners of collaboration also become practitioners of solidarity economies, looking at shared livelihoods as always already part of shared production.

Money and debt is a loaded topic for artists, and yet you face debt and economic precarity head on in projects like “BFAMFAPHD.” How did that project come about? Why did you decide to take on that topic?

Caroline Woolard, Emilio Martinez Poppe, and Susan Jahoda for BFAMFAPhD. Of Supply Chains, 2016. Courtesy of BFAMFAPhD, photo CC-BY-ND 4.0

In the classroom, arts educators confront the socially idealized occupation of the cultural producer and the frequent disavowal of a relationship between cultural production and the contemporary political economy. It is my aim to articulate existing economies of cultural production as well as plausible futures of cooperation in art. I do this in my teaching, scholarship, and independent work. Most recently, my co-authored articles (On the Cultural Value Debate) and teaching tools (Of Supply Chains) speak to these concerns. In Of Supply Chains, co-authored with Susan Jahoda and co-designed with Emilio Reynaldo Martinez Poppe, a recent graduate of Cooper Union, we write:

“We aim to articulate the relationship between art making, pedagogy, and political economy. We believe that practices of collaboration and solidarity economies are foundational for contemporary visual arts, design, and new media education. ” Our text, workbook, and game are online this month. For now, you can see an early version of our game here.

You have described NYCREIC as “creative commons for land.” Can you elaborate on that statement?

Caroline Woolard, Exchange Cafe, 2013. Photo courtesy of MoMA, CC-BY-ND 4.0

Just as Creative Commons provides a legal framework for authors to easily share their intellectual property, I believe that we need an entity to provide legal frameworks for land owners to share their land easily. This is what I would call a “Creative Commonwealth.” The New York City Real Estate Investment Cooperative, and so many initiatives related to community land trusts, could be considered examples of projects that would utilize the Creative Commonwealth framework, if it existed. Janelle Orsi at the Sustainable Economies Law Center, is working on something of this nature with the Agrarian Trust.

How do you see investment in affordable physical space as essential to a commons?

Since co-founding and co-directing OurGoods.org and TradeSchool.coop in 2008 to enable resource sharing, I’ve seen how solidarity economy platforms build resilience and mutual aid — often for those of us on the privileged side of the digital divide. I’ve also seen that online platforms are not enough. All people need affordable space, so that they can take risks and fail. Where will we meet to swap or share goods and services without affordable space? Ensuring affordable space is the only way creativity and innovation can occur. And so I started thinking: How might we as artists utilize the strengths of a networked information era to cooperatively finance, acquire, and manage space? What can artists do to help ensure affordable space and reduce displacement?

You’ve used open licensing in a variety of projects like “Queer Rocker” and “Origin of the World Dress.” Why did you decide to open source your work? Have there been any surprising outcomes?

The Queer Rocker is an example of what I call a Free/Libre/Open Source Systems and Art project. I made the designs, files, and assembly process for the Queer Rocker available for use and modification because I learn by doing, and by uniting research with action. I want to furnish gathering spaces with objects that are as imaginative as the conversations that occur in those spaces. I want to contribute to an economy of social justice, solidarity, sustainability, and cooperation. I hope to add spaces of reflection and healing to social movements, so many of which are, at present, focused on immediate protest and progress. Many students, activists, and grassroots organizations cannot afford to purchase furniture, but they may have time to create things with the materials around them.

Posted 23 August 2016My aim with open source projects is that through communal production and alteration, a radical politics will emerge; a politics of cooperation.