Help us protect the commons. Make a tax deductible gift to fund our work in 2025. Donate today!

The Commons Opens Up the World

EventsCynthia Khoo on net neutrality, where creativity comes from, and getting involved with the Creative Commons Summit

Based in Toronto, Cynthia Khoo is an internet and technology lawyer working at the intersection of digital rights, copyright and freedom of expression. In advance of the Creative Commons Global Summit, we’re gathering the stories of inspiring humans working around the world to shape the Commons’ future. We want to share your story, too — drop by the “Humans of the Commons” listening lounge at the Summit to get interviewed and add your voice. Here’s an edited transcript of Cynthia’s story:

I first got involved with Creative Commons last year when the Creative Commons Global Summit happened in Toronto. I had just moved to Toronto, so it seemed like a great opportunity to see what the organization did firsthand. The summit was an amazing experience; I loved it. It felt unlike other conferences I’d been to up to that point.

After that I went from just being aware of Creative Commons to actively wanting to be a part of it. I got added to the Creative Commons Slack – I hung out for a bit, just to see what was up and keep an eye out for ways to get involved. I was working with Open Media at the time on their copyright reform platform, and because Creative Commons is in that space as well we found opportunities to collaborate together.

So when the opening came up for volunteers to help organize this year’s summit, I thought it would be an amazing opportunity to help out and pay it forward.

“Yes! They got it!!”

One recent success I’m really proud of is a significant victory for net neutrality here in Canada. Net neutrality is under serious threat in the U.S. and around the world right now, and last year’s hearing was similarly critical for Canada. It focused on “zero rating,” which is about whether phone and cable companies should be allowed to discriminate or privilege some content on your mobile phone data plan, like certain music or video services.

One of the challenges we faced from the parties on the opposing side, I thought, was a misrepresentation around how our internet access is structured. Their argument conflated two very different layers: the access component of going online, and the content component. If you think of a layer cake, it was like they were trying to cut through both layers of the cake and serve them to consumers as slices. That would essentially be a form of Internet rationed out to users piece by piece, as opposed to a neutral Internet connection that’s essential for access to information and freedom of expression.

I wanted to make it really clear that wasn’t an accurate characterization of how the system actually works. We had to figure out how to make the Commissioners see that there are reasons we need to keep those layers distinct, going back to basic telecom principles like common carriage and non-discrimination between users in similar situations. That was something I spent a lot of time trying to think through, because they came at that argument from several different angles.

When the decision came out, the Commissioners explicitly cited some of the arguments that we had made and language we had used. Other public interest groups and individuals intervened in the case and made similar arguments — but it was important to me and I had spent so much time on it… I just had this moment of: “Yes! They got it!!”

We ended up winning the case. There’s some debate about how strongly they ruled in our favor, but they established a framework that was along the lines of what we were arguing for.

“Where’s the line between imitation and inspiration?”

I believe the greatest threat to the Commons today is disproportionate copyright enforcement. That has a number of effects and attacks the Commons from multiple angles.

Copyright enforcement itself is of course fine, and we need it; artists and creators should have their work protected and get due compensation for it. But when copyright enforcement becomes disproportionate, things go off the rails. That’s where you end up with mis-ranked priorities — like placing some publishers’ royalties above freedom of expression or above access to information.

So much of creation, whether it’s music or film writing, is iterative. It’s based on the past.

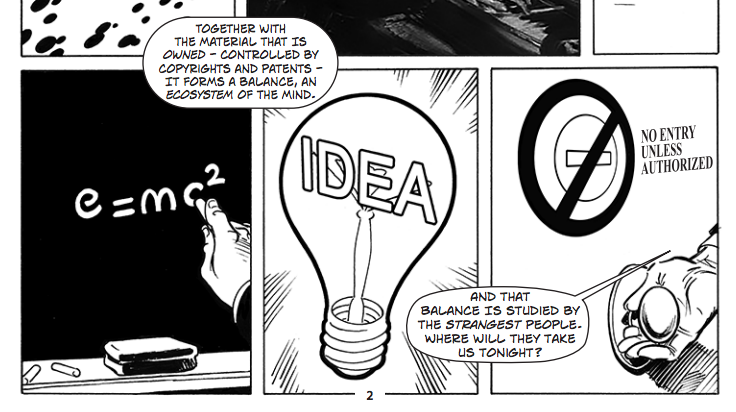

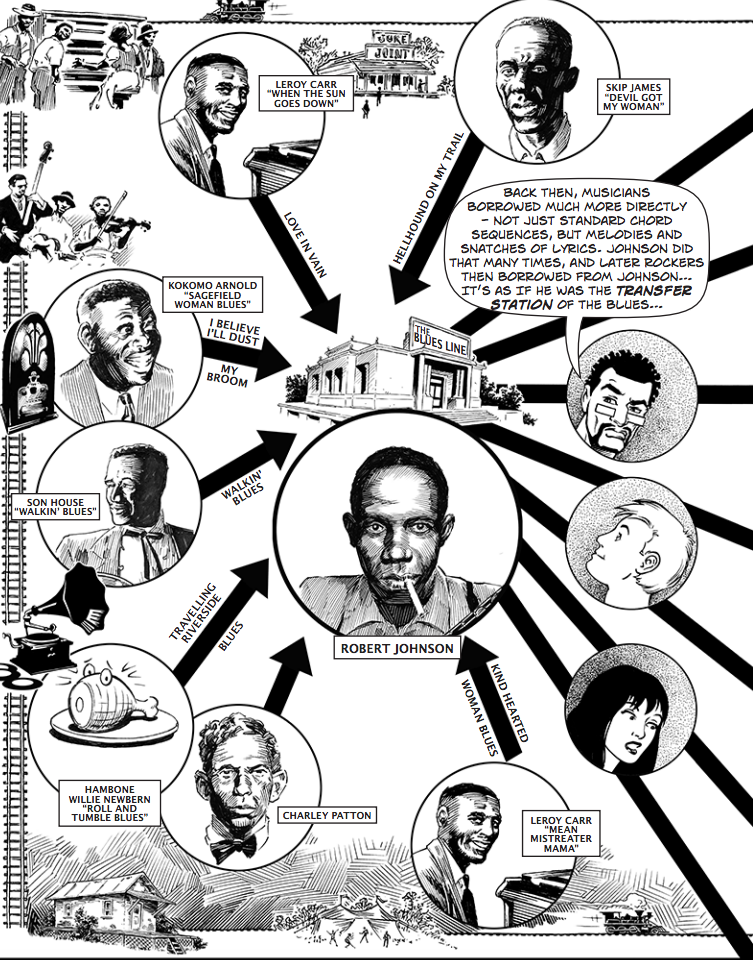

Disproportionate copyright enforcement also stops new things from even being created in the first place, because so much of creation, whether it’s music or film writing, is iterative. It’s based on the past.

There’s this amazing graphic novel called Theft: A History of Music about how music is based on imitation and iteration and inspiration. Where’s the line between imitation and inspiration?

If modern-day copyright laws existed in the past, it’s possible things like jazz or blues wouldn’t even exist today at all.

They would have been sued out of existence. The type of music deemed “worthy” of copyright had a racialized aspect as well. A lot of Westernized classical music, for example, was protected because the melody was considered copyrightable. But other types of music – music that was more beats-based or rhythms-based and associated with African-American musicians – the courts found was not copyrightable. That appears to be based more on a cultural difference than something inherent in the music itself. So when you have that kind of selective enforcement, is it really about creators’ rights? Or is it actually about power and concentrating control?

From Theft: A History of Music CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

“Nothing in the world is equally distributed right now”

Access to information, freedom of expression, diversity, social progress, social, political, and economic equality — all of these things are advanced by a vibrant Commons. The Commons opens up the world. It opens different aspects of the world to different groups of people for whom it might otherwise be closed.

It’s only by removing unfair barriers that we will get to a better world.

That’s so important because nothing in the world is equally distributed right now. Everything is unfairly distributed — because you happen to be born into a rich family, say, or happen to be born in Canada. A vibrant Commons is where these things come out, and it provides a way to remove some of those unfair barriers. And it’s only by removing unfair barriers that we will get to a better world.

Posted 12 April 2018