Help us protect the commons. Make a tax deductible gift to fund our work. Donate today!

Traditional Knowledge Labels

Joining us at the Creative Commons Global Summit in 2018, NYU professor and legal scholar Jane Anderson presented the collaborative project “Local Contexts,” “an initiative to support Native, First Nations, Aboriginal, Inuit, Metis and Indigenous communities in the management of their intellectual property and cultural heritage specifically within the digital environment.” The wide-ranging panel touched on the need for practical strategies for Indigenous communities to reclaim their rights and assert sovereignty over their own intellectual property.

Anderson’s work on Local Contexts is a collaboration with Kim Christen, creator of the Mukurtu content management system and Director of the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation at Washington State University. Local Contexts is both a legal and educational project that engages with the specific challenges and difficulties that copyright poses for Indigenous peoples seeking to access, use and control the circulation of cultural heritage. Inspired by the intervention of Creative Commons licenses at the level of metadata, the Traditional Knowledge Labels recast intellectual property as culturally determinant and dependent upon cultural consent to use of materials.

How can we have an open movement that works for everyone, not only the most powerful? How have power structures historically worked against Indigenous communities, and how can the Creative Commons community work to change this historic inequality?

Jane Anderson discussed these issues as well as some of her more recent work with the Passamaquoddy Tribe in Maine with Creative Commons.

Your project recasts the Creative Commons vision of “universal access to research and education and full participation in culture” through a local and culturally determinant lens. How is the vision of Local Contexts complementary to the CC vision, and how does it come into conflict?

The Local Contexts initiative began in 2010 when Kim Christen and I started to think more carefully about how to support Indigenous communities to address the immense and growing problems being experienced with copyright around Indigenous or traditional knowledge. We had both been working with Indigenous peoples, communities and organizations over a long period of time and had increasingly been engaged in a very specific way with the dilemmas of copyright that existed at the intersection of Indigenous collections in archives, libraries and museums. We were able to see more clearly the ways in which copyright has functioned as a key tool for dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their rights as holders, custodians, authorities and owners of their knowledge and culture.

Combining both legal and educational components, Local Contexts has two objectives. Firstly, to support Indigenous decision-making and governance frameworks for determining ownership, access to and culturally appropriate conditions for sharing historical and contemporary collections of Indigenous material and digital culture. Secondly, to trouble existing classificatory, curatorial and display paradigms for museums, libraries and archives that hold extensive Indigenous collections by finding new pathways for Indigenous names, perspectives, rules of circulation and the sharing culture to be included and expressed within public records.

Inspired by Creative Commons, we began trying to address the gap for Indigenous communities and copyright law by thinking about licenses as an option to support Indigenous communities.

Our initial impulse was to craft several new licenses in ways that incorporated local community protocols around the sharing of knowledge. Pretty quickly however we ran into a significant problem: with the majority of photographs, sound recordings, films, manuscripts, language materials that had been amassed and collected about Indigenous peoples, and that were now being digitized, Indigenous peoples were not the copyright holders. Instead, copyright was held by the researchers, missionaries or government officials who had done the documenting or by the institutions where these materials were now held. Or – at the other end of the spectrum, these materials were in the unique space that copyright makes – the public domain. This meant that not only did Indigenous peoples have no control over these materials and their circulatory futures, they also could not apply any licenses – either CC ones or ones that we were developing. This was a problem that we responded to by developing the TK Labels.

Why is it important to problematize the ways in which universal access can undermine cultural participation, particularly for traditionally marginalized groups?

Local Contexts is an effort to initiate questions about how ideas of the universal operate by pointing to sites of difference and locality, especially in how knowledge is shared, circulated and expanded. The vision of Local Contexts emphasizes specificity – that the circulation of knowledge and culture depends upon relationships and context – and if these relationships are formed unevenly, or privilege one cultural perspective above another, then that inequity continues to create a range of future problems.

One of the motivations behind Local Contexts, and this is an interesting question for Creative Commons to consider as well is: what would it look like if we invested time and support to Indigenous communities who have been disproportionately affected by colonial property laws – including copyright. How does access and openness perpetuate a colonial agenda of taking? And what can be done to change this direction? Where does the Creative Commons community come in to help think through these issues in conversation with Indigenous peoples and through Indigenous experiences? Is it possible to decolonize the commons? What would it look like to imagine a commons that is not totally open, but one that has an informed and engaged approach to openness; one that foregrounds the histories and exclusions embedded within calls for openness and open access. What would it mean to ask questions about the privilege that openness calls for and embeds?

We believe that Local Contexts is one of many efforts that are needed in order to take on this expansive problem. If you start thinking about what kind of information has been taken (through unethical and inappropriate research practices for instance) from Indigenous peoples, communities, lands and territories – and how this has been done without consent and permission, it is possible to start seeing the extent of the problem. For example, Indigenous names have been used for names of cars (Cherokee); for software (Apache); for varieties of strawberries (Sto:lo). For Indigenous peoples, names are not just words in common, they have embedded temporal and relational meanings including integral connections to place. For Indigenous peoples, names matter and are not open for others to use in ways that minimize and reduce them for commercial gain. How have settler-colonial laws and social frameworks created the conditions where no permissions are required to use Indigenous culture? What is the impetus to use Indigenous culture in these ways? Who benefits from using these exclusionary and extractionist logics?

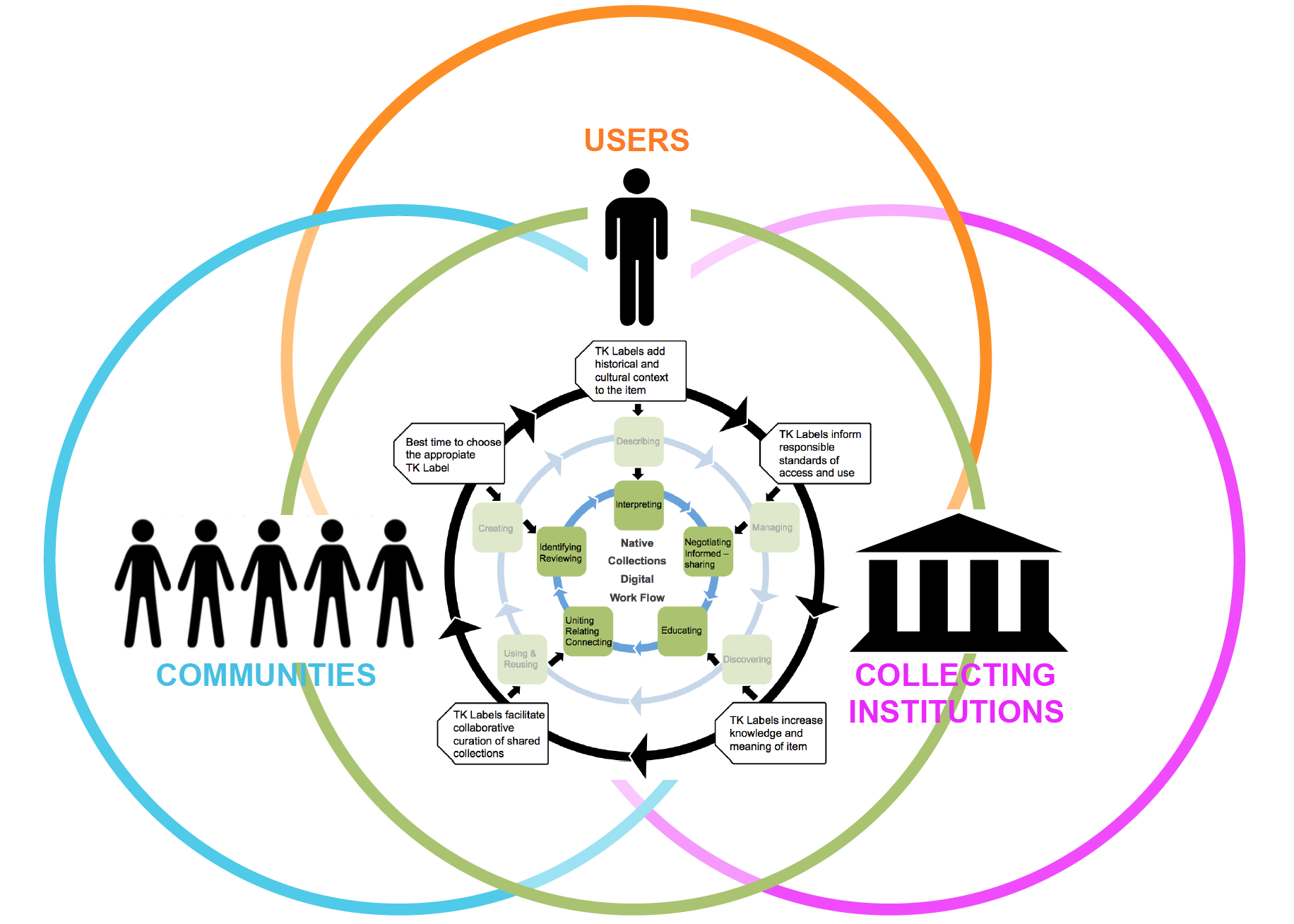

Reciprocal Curation Workflow

How does information colonialism impact the communities where you work? How are you working to mitigate exploitation of cultural resources?

Information colonialism is an everyday problem for all the communities with whom we work and collaborate. It is not only the legacies of past research practices, but how these are continued into the present. There are more researchers working in Indigenous communities now than there were at the height of initial colonial documenting encounters from the 1850s onwards – and the same logics of extraction through research largely continue. This means that many of the same problems that we are trying to address in Local Contexts – namely the making of research derived from Indigenous knowledge and participation often conducted on Indigenous lands as owned by non-Indigenous peoples – continues.

There is an enormous need to support Indigenous communities as they build their own unique IP strategies and provide resources that assist in this project. At Local Contexts we are committed to this work and we provide as many resources as we can towards this end. Importantly we work directly with communities, and the resources we produce and offer come from these partnerships. We continue to develop tools and resources from direct engagement with communities. Partnering with the Penobscot Nation we just received an IMLS grant to run IP training and support workshops for US based tribes over the next two years. These trainings center Indigenous experiences with copyright law and the difficulties communities have negotiating with cultural institutions over incorporating cultural authority into how these Indigenous collections are to be circulated into the future.

The 6 CC licenses are designed to be simple and self-explanatory, but there are 17 Traditional Knowledge labels and four licenses, creating an intentionally local and culturally dependent information ecosystem. As a project both inspired by the Creative Commons licenses and in conversation with them, how do these labels better serve the contexts in which you work?

The 17 TK Labels that we have reflect partnerships that have identified these protocols as ones that that matter for communities in the diverse circulation routes for knowledge. What is important about the TK Labels part of the Local Contexts initiative is that they are deliberately not licenses. That is, we are not limited by the cultural (in)capacities of the law. Indigenous protocols around the use of knowledge are nuanced and complex and do not map easily onto current legal frameworks. For instance, some information should never be shared outside a community context, some information is culturally sensitive, some information is gendered, and some has specific familial responsibilities for how it is shared. Some information should only be heard at specific times of the year and still for other information, responsibility for use is shared across multiple communities.

The Labels embrace this epistemological complexity in a different kind of way – and they allow for flexibility as well as community specificity to be incorporated in ways that settler-colonial law cannot accommodate.

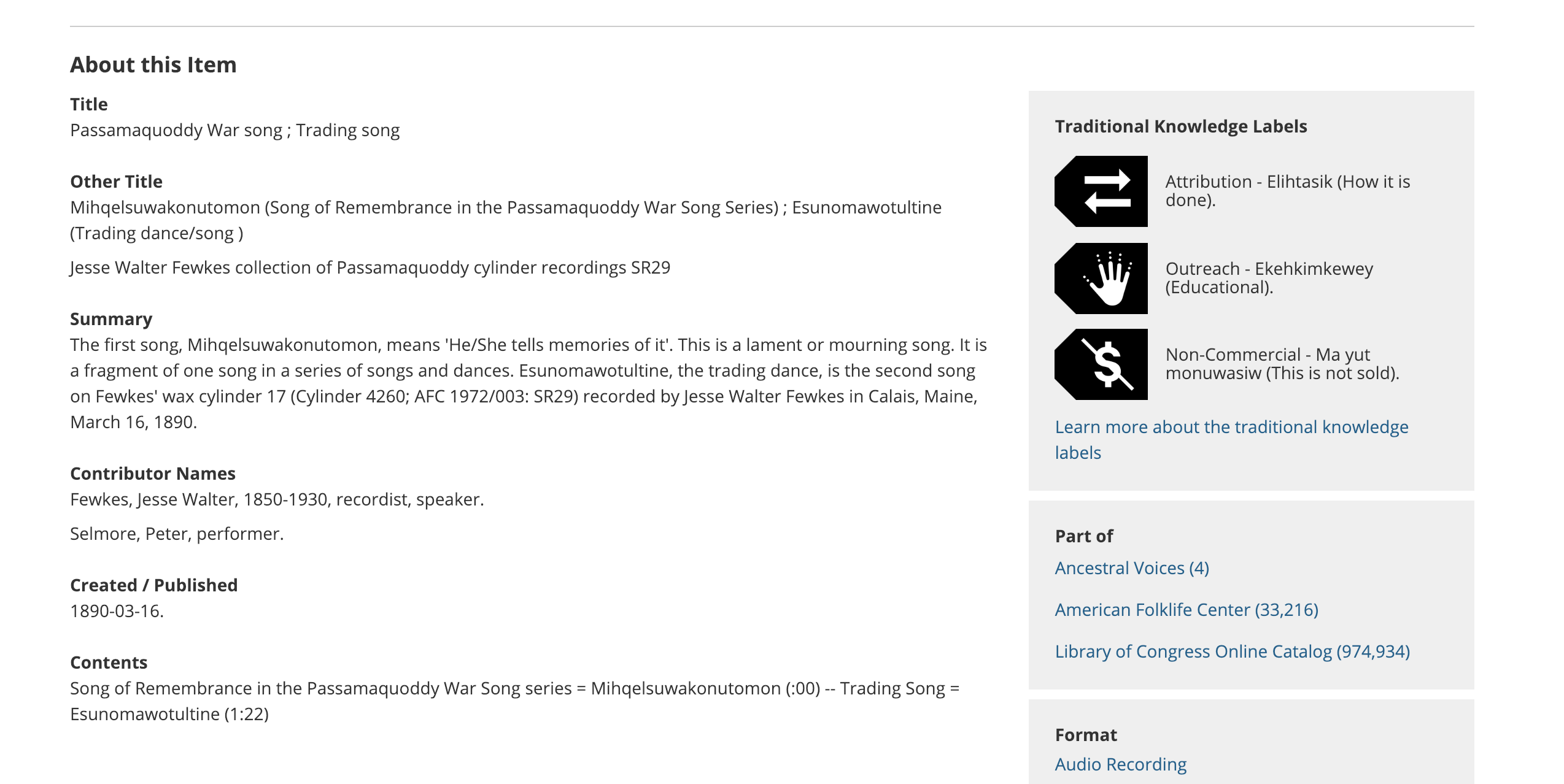

For instance, a central pivot of the TK Labels project from CC is that the TK Label icon remains static, but the text that accompanies each Label can be uniquely customized by each community and they maintain the control and the authority over the text. This is the sovereign right that every community has to determine and express their unique cultural protocols. Alongside this, the TK Labels also expand the meaning of certain kinds of legal terms, which have been historically treated as normative – for instance, attribution. With the TK Labels – attribution is usually the first label that a community identifies and adapts for their own purposes. This is because it has been Indigenous names – community, individual, familial that have been left out of the catalogue and the metadata. For example, the Sq’ewlets, a band of Sto:lo in Canada translated attribution as skwix qas te téméxw, which literally means name and place. (See how they use their labels.) For the Passamaquoddy Tribe in Maine, attribution is Elihatsik translated “to fix it properly”. The intention in the Passamaquoddy meaning of attribution is a specific call out for addressing mistakes in an institutional and therefore also in settler cultural memory.

What is one interesting outcome of your recent work?

One of our most important recent projects has been working with the Passamaquoddy Tribe to digitally repatriate and correct the cultural authority that the Passamaquoddy people continue to assert over the first Native American ethnographic sound recordings ever made in the US in 1890. When these recordings were made by a young researcher who visited the community for three days, they functioned as a sound experiment allowing for greater documentation of Indigenous peoples languages and cultures. The recordings were never made for the Passamaquoddy community but for researchers in institutions. This is evidenced by the fact that these recordings were not returned to the community until the 1980s – some 90 years after they were made. When this initial return, on cassette tapes, happened in the 1980s, the quality of the sound was poor. For community members thrilled to hear ancestors again after so long it was simultaneously heartbreaking not being able to hear what was being said.

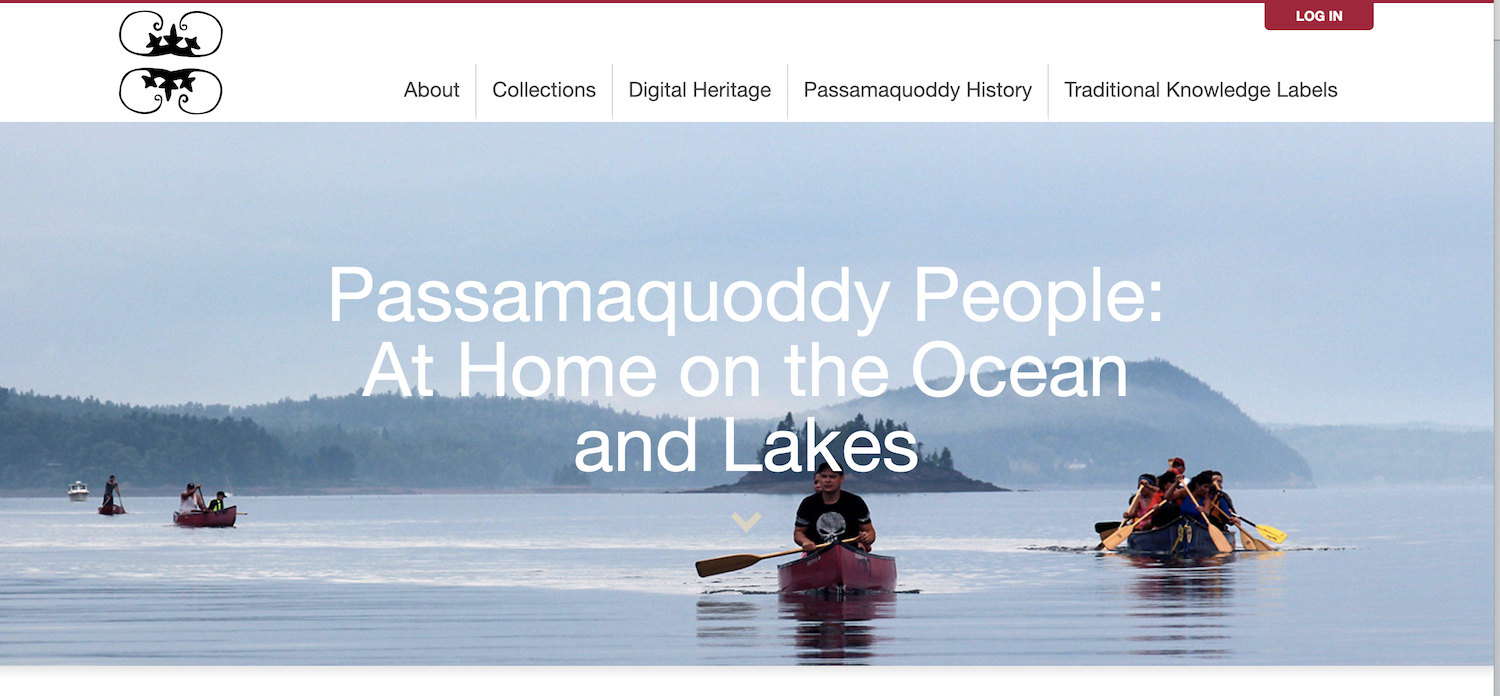

From Passamaquoddy People Website

In 2015, the Library of Congress’ National Audiovisual Conservation Center (NAVCC) included these cylinders in their digital preservation program for American and Native American heritage. At the same time as this preservation work was initiated, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, the Passamaquoddy Tribe, Local Contexts and Mukurtu CMS joined together for the Ancestral Voices Project funded by the Arcadia Foundation. This project involved working with Passamaquoddy Elders and language speakers to listen, translate and retitle the recordings in English and, for the first time in the historical record in Passamaquoddy; explaining and updating institutional knowledge about the legal and cultural rights in these recordings; adding missing and incomplete information and metadata; fixing mistakes in the Federal Cylinder Project record and implementing three Passamaquoddy TK Labels. These add additional cultural information to the rights field of the digital record – in both the MARC record and in Dublin core – and provide ongoing support for how these recordings will circulate digitally into the future.

Library of Congress record with TK labels

Changing how these recordings are understood in the Library of Congress and in the metadata into the future was only one part of this project. A complimentary part was working with the Passamaquoddy community to create their own digital platform for the cylinders, embedding them and relating them to other Passamaquoddy cultural heritage. The Passamaquoddy site utilizes the Mukurtu CMS platform and allows for differentiated access at a community level and for various other publics. It does not assume that everything created by Passamaquoddy people is for everyone, including non-Passamaquoddy people. It embeds Passamaquoddy cultural protocols as the primary means for managing access according to Passamaquoddy laws. This is then what is also translated into the Library of Congress through the TK Labels.

Working with Passamaquoddy Elders and language speakers to decipher the cylinders and for tribal members to now be singing these songs and teaching them to their children was what the work within this project required. When the Passamaquoddy recordings with community determined metadata and TK Labels were launched at the Library of Congress in May 2018, Dwayne Tomah called on the strength of his ancestors, and sang a song that had not been sung for 128 years. The ongoing strength of Passamaquoddy culture, language and Passamaquoddy survivance was felt by everyone who was in the room that day. The TK Labels were an important piece of this project as they functioned as a tool to support the correcting of a significant mistake in the historical record: namely that the Passamaquoddy people unreservedly retain authority over their culture which had been literally taken and authored by a white researcher from 1890 until 2018. (Read more in the New Yorker.)

What are you working on now?

At an international and national level, the TK Labels are an intervention directed at the level of metadata—the same intervention that propelled CC licenses to the reach they have today. Our current work at Local Contexts is threefold. We are finalizing the TK Label Hub. This will allow for a more widespread implementation of the TK Labels. It will be the place where communities can customize their Labels and safely deliver them to the institutions that request them and are committed to implementing them within their own institutional infrastructures and public displays. Our current work with the Abbe Museum in Maine will see the TK Labels integrated into the Past Perfect software as well, allowing for implementation across a wide museum sector. We continue to expand our education work on IP law and Indigenous collections for communities as well as institutions. More generally we believe that any education on copyright must have the history and consequences of excluding Indigenous peoples from this body of law incorporated into how it is taught and understood.

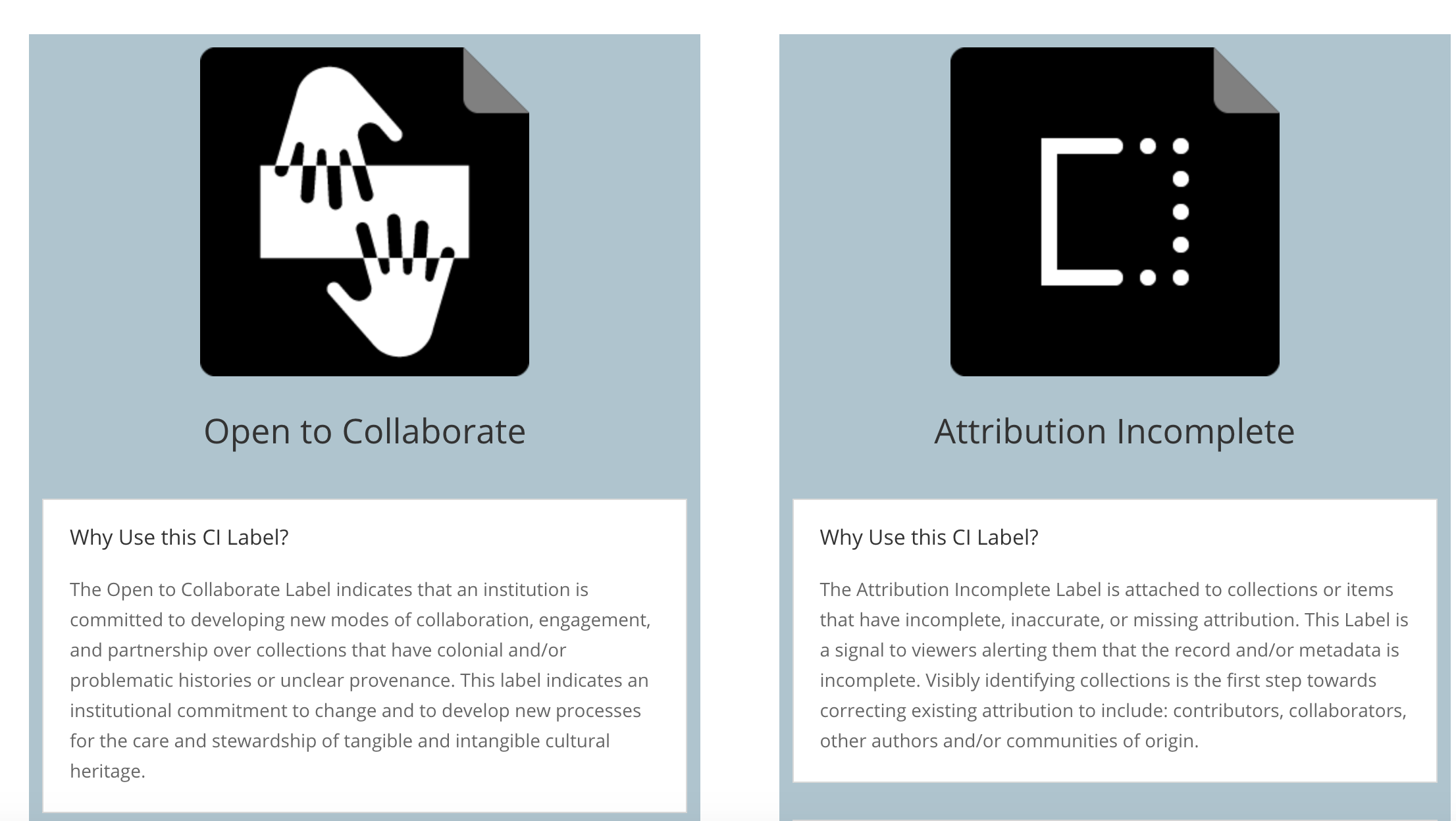

Finally we just developed 2 specific labels for cultural institutions. The Cultural Institution (CI) Labels are specifically for archives, museums, libraries and universities who are engaging in processes of collaboration and trust building with Indigenous and other marginalized communities who have been excluded and written out of the record through colonial processes of documentation and record keeping.

These CI Labels, alongside the TK Labels for communities and our education/training initiatives help close the circle, so that the future circulation of these cultural heritage materials, that have been held outside of communities, can be informed through relationships of care, responsibility and authority that reside within the local contexts where this material continues to have extensive cultural meaning.

Read more about the role that CC licenses play in the dissemination of traditional knowledge from our research fellow Mehtab Khan and listen to Jane Anderson speak about her work with the Passamaquoddy archives on the podcast “Artist in the Archive.”

Posted 30 January 2019