Help us protect the commons. Make a tax deductible gift to fund our work. Donate today!

The new book Open: The Philosophy and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science, edited by Rajiv Jhangiani and Robert Biswas-Diener, features the work of open advocates around the world, including Cable Green, Director of Open Education at Creative Commons. This excerpt from his chapter, “Open Licensing and Open Education Licensing Policy,” provides a summary of open licensing for education, as well as delves into the philosophical and technical underpinnings of his work in “open.”

Read and download the entire book via Ubiquity Press and follow Cable on Twitter @cgreen.

Open Licensing

Long before the internet was conceived, copyright law regulated the very activities the internet, cheap disc space and cloud computing make essentially free (copying, storing, and distributing). Consequently, the internet was born at a severe disadvantage, as preexisting copyright laws discouraged the public from realizing the full potential of the network.

Since the invention of the internet, copyright law has been ‘strengthened’ to further restrict the public’s legal rights to copy and share on the internet. For example, in 2012 the US Supreme Court on upheld the US Congress’s right to extend copyright protection to millions of books, films, and musical compositions by foreign artists that once were free for public use. Lawrence Golan, a University of Denver music professor and conductor who challenged the law on behalf of fellow conductors, academics and film historians said ‘they could no long afford to play such works as Sergei Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf,” which once was in the public domain but received copyright protection that significantly increased its cost.’

While existing laws, old business models, and education content procurement practices make it difficult for teachers and learners to leverage the full power of the internet to access high-quality, affordable learning materials, OER can be freely retained (keep a copy), reused (use as is), revised (adapt, adjust, modify), remixed (mashup different content to create something new), and redistributed (share copies with others) without breaking copyright law. OER allow the full technical power of the internet to be brought to bear on education. OER allow exactly what the internet enables: free sharing of educational resources with the world.

What makes this legal sharing possible? Open licenses. The importance of open licensing in OER is simple. The key distinguishing characteristic of OER is its intellectual property license and the legal permissions the license grants the public to use, modify, and share it. If an educational resource is not clearly marked as being in the public domain or having an open license, it is not an OER. Some educators think sharing their digital resources online, for free, makes their content OER — it does not. Though it is OER if they go the extra step and add an open license to their work.

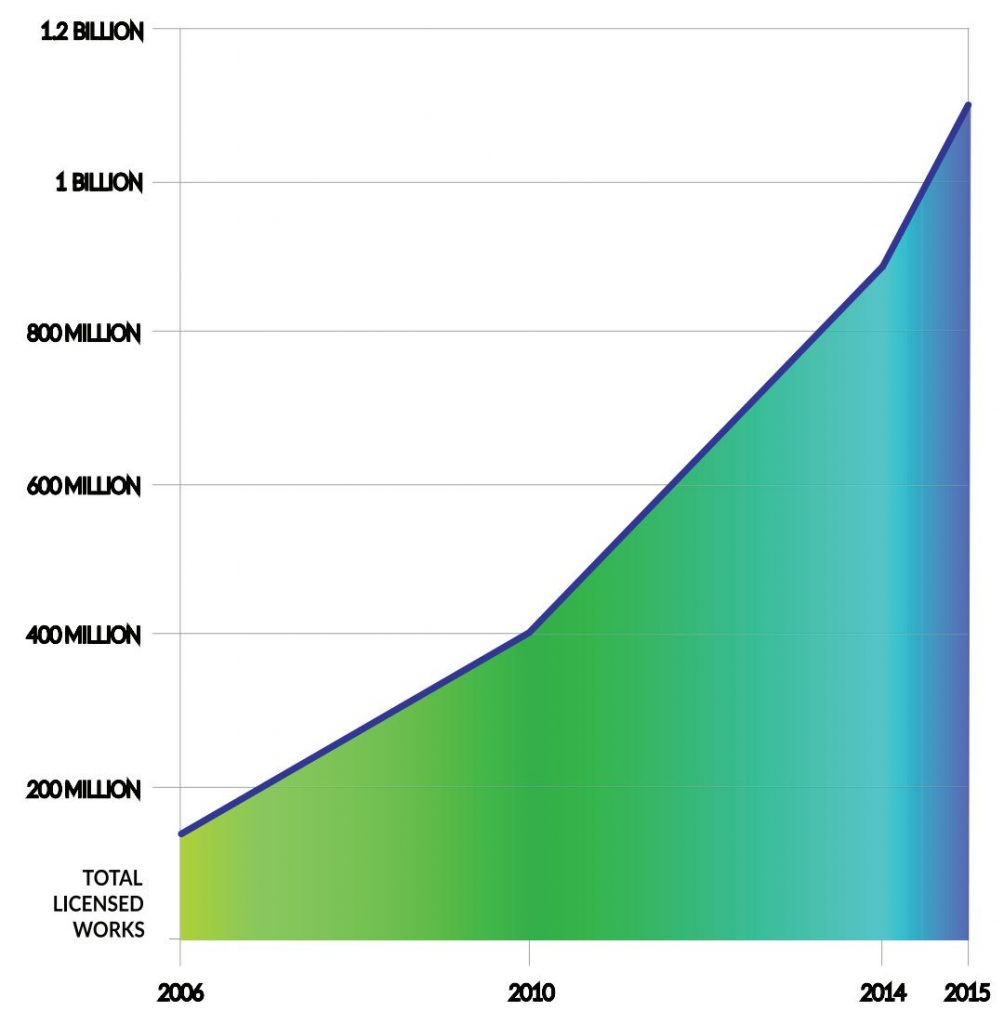

The most common way to openly license copyrighted education materials — making them OER − is to add a Creative Commons license to the educational resource. CC licenses are standardized, free-to-use, open copyright licenses that have already been applied to more than 1.2 billion copyrighted works across 9 million websites.

Collectively, CC licensed works constitute a class of educational works that are explicitly meant to be legally shared and reused with few restrictions. David Bollier writes:

‘Like free software, the CC licenses paradoxically rely upon copyright law to legally protect the commons. The licenses use the rights of ownership granted by copyright law not to exclude others, but to invite them to share. The licenses recognize authors’ interests in owning and controlling their work — but they also recognize that new creativity owes many social and intergenerational debts. Creativity is not something that emanates solely from the mind of the “romantic author,” as copyright mythology has it; it also derives from artistic communities and previous generations of authors and artists. The CC licenses provide a legal means to allow works to circulate so that people can create something new. Share, reuse, and remix, legally, as Creative Commons puts it.’

While custom copyright licenses can be developed to facilitate the development and use of OER, it may be easier to apply free-to-use, global standardized licenses developed specifically for that purpose, such as those developed by Creative Commons.

Fig. 1: Annual Growth of CC licensed works.

Open Education Licensing Policy

This section explores how public policymakers can leverage open licensing policies, and by extension OER, as a solution to high textbook costs, out-of-date educational resources and disappearing access to expensive, DRM protected e-books. Education policy is about solving education problems for the public. If one of the roles of government is to ensure all of its citizens have access to effective, high-quality educational resources, then governments ought to employ current, proven legal, technical, and policy tools to ensure the most efficient and impactful use of public education funding.

Open education policies are laws, rules, and courses of action that facilitate the creation, use or improvement of OER. While this chapter only deals with open education licensing policies, there has also been significant open education resource-based (allocate resources directly to support OER), inducement (call for or incentivize actions to support OER), and framework (create pathways or remove barriers for action to support OER) open education policy work.

Open education licensing policies insert open licensing requirements into existing funding systems (e.g., grants, contracts, or other agreements) that create educational resources, thereby making the content OER, and shifting the default on publicly funded educational resources from ‘closed’ to ‘open.’ This is a particularly strong education policy argument: if the public pays for education resources, the public should have the right to access and use those resources at no additional cost and with the full spectrum of legal rights necessary to engage in 5R activities.

My friend David Wiley likes to say ‘if you buy one, you should get one.’ David, like most of us, believes that when you buy something, you should actually get the thing you paid for. Provincial/state and national governments frequently fund the development of education and research resources through grants funded with taxpayer dollars. In other words, when a government gives a grant to a university to produce a water security degree program, you and I have already paid for it. Unfortunately, it is almost always the case that these publicly funded educational resources are commercialized in such a way that access is restricted to those who are willing to pay for them a second time. Why should we be required to pay a second time for the thing we’ve already paid for?

Governments and other funding entities that wish to maximize the impacts of their education investments are moving toward open education licensing policies. National, provincial/state governments, and education systems all play a critical role in setting policies that drive education investments and have an interest in ensuring that public funding of education makes a meaningful, cost-effective contribution to socioeconomic development. Given this role, these policy-making entities are ideally positioned to require recipients of public funding to produce educational resources under an open license.

Let us be specific. Governments, foundations, and education systems/institutions can and should implement open education licensing policies by requiring open licenses on the educational resources produced with their funding. Strong open licensing policies make open licensing mandatory and apply a clear definition for open license, ideally using the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license that grants full reuse rights provided the original author is attributed. The good news is open education policies are happening! In June 2012, UNESCO convened a World OER Congress and released a 2012 Paris OER Declaration, which included a call for governments to ‘encourage the open licensing of educational materials produced with public funds.’ UNESCO will be convening a second World OER Congress in Slovenia in 2017 to establish a ‘normative instrument on OER.’ OECD recently released its 2015 report: ‘Open Educational Resources: A Catalyst for Innovation’ provides policy options to governments such as: ‘Regulate that all publicly funded materials should be OER by default. Alternatively, the regulation could state that new educational resources should be based on existing OER, where possible (“reuse first” principle).’

As governments and foundations move to require the products of their grants and/or contracts be openly licensed, the implementation stage of these policies critical; open licensing policies should have systems in place to ensure that grantees comply with the policy, properly apply an open license to their work, and share an editable, accessible version of the OER in a public OER repository.

A good example of an open education licensing policy done well is the US Department of Labor’s 2010 Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training Grant Program (TAACCCT) which committed US$2 billion in federal grant funding over four years to ‘expand and improve their ability to deliver education and career training programs’ (p.1). The intellectual property section of the grant program description requires that all educational materials created with grant funding be licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, and the Department required its grantees to deposit editable copies of the CC BY OER into skillscommons.org — a public open education repository.

A number of other nations, provinces and states have also adopted or announced open education policies relating to the creation, review, remix and/or adoption of OER. The Open Policy Registry lists over 130 national, state, province, and institutional policies relating to OER, including policies like a national open licensing framework and a policy explicitly permitting public school teachers to share materials they create in the course of their employment under a CC license.

New open policy projects like the Open Policy Network and the Institute for Open Leadership are well positioned to foster the creation, adoption, and implementation of open policies and practices that advance the public good by supporting open policy advocates, organizations, and policy makers, connecting open policy opportunities with assistance, and sharing open policy information. Because the bulk of education and research funding comes from taxpayer dollars, it is essential to create, adopt and implement open education licensing policies. The traditional model of academic research publishing borders on scandalous. Every year, hundreds of billions in research and data are funded by the public through government grants, and then acquired at no cost by publishers who do not compensate a single author or peer reviewer, acquire all copyright rights, and then sell access to the publicly funded research back to the University and Colleges. In the US, the combined value of government, non-profit, and university-funded research in 2013 was over US$158 billion — about a third of all the R&D in the United States that year.

As governments move to require open licensing policies, hundreds of billions of dollars of education and research resources will be freely and legally available to the public that paid for them. Every taxpayer − in every country − has a reasonable expectation of access to educational materials and research products whose creation tax dollars supported.

Posted 05 June 2017