Artificial Intelligence and Creativity: Why We’re Against Copyright Protection for AI-Generated Output

CopyrightShould novel output (such as music, artworks, poems, etc.) generated by artificial intelligence1 (AI) be protected by copyright? While this question seems straightforward, the answer certainly isn’t. It brings together technical, legal, and philosophical questions regarding “creativity,” and whether machines can be considered “authors” that produce “original” works.

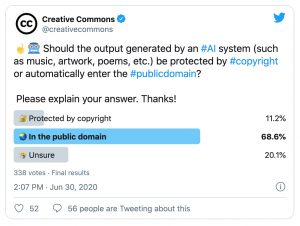

A screenshot of our June 2020 Twitter Poll results.

In search of an answer, we ran an admittedly unscientific Twitter poll over five days in June. Interestingly, almost 70% of a total of 338 respondents indicated that novel outputs from an AI system belong in the public domain, while 20% weren’t sure. For example, one commentator said that “since an AI will (given the same inputs and the same model) produce the same output every time, it’s hard to argue it’s unique and creative,” another succinctly argued: “system-generated activities = no creative input, therefore, no copyright,” while another respondent noted that it “depends on the nature of the AI, and the source materials used…I don’t think you could make a blanket rule for all AI.” This question was also debated at the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) Conversation on Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence (Second Session) held from 7-9 July 2020. To share our general policy views on this topic from a global perspective, Creative Commons submitted a written statement and made two oral interventions (here and here).

In this blog post, the first in a series on AI and creativity, we explore some of the fundamentals of copyright protection in an attempt to determine whether AI is capable of creating works eligible for copyright protection. In the second blog post, “Artificial Intelligence and Creativity: Can Machines Write Like Jane Austen?“ we walk you through two practical examples of an AI system generating arguably novel content and apply copyright eligibility criteria to them. By doing so, we hope to shed light on some of the copyright issues arising around the nascent field of AI technology.

What works can benefit from copyright protection?

In order to determine what constitutes a creative work eligible for copyright protection, most national copyright regimes rely on the concepts of authorship and originality, among others.

The concept of authorship

For a work to be protected by copyright, there needs to be creative involvement on the part of an “author.” At the international level, the Berne Convention stipulates that “protection shall operate for the benefit of the author” (art 2.6), but doesn’t define “author.” Likewise, in the European Union (EU) copyright law,2 there is no definition of “author” but case-law has established that only human creations are protected.3 This premise is reflected in the national laws of countries of civil law tradition, such as France, Germany, and Spain, which state that works must bear the imprint of the author’s personality. As AI systems do not have a personality that they could imprint on what they produce, authorship is beyond limits for AI.

This “selfie” taken by a Macaca nigra female in 2011 after picking up photographer David Slater’s camera in Indonesia. It was at the heart of the monkey selfie copyright dispute. Access it here.

In countries of common law tradition (Canada, UK, Australia, New Zealand, USA, etc.), copyright law follows the utilitarian theory, according to which incentives and rewards for the creation of works are provided in exchange for access by the public, as a matter of social welfare. Under this theory, personality is not as central to the notion of authorship, suggesting that a door might be left open for non-human authors. However, the 2016 Monkey selfie case in the US determined that there could be no copyright in pictures taken by a monkey, precisely because the pictures were taken without any human intervention. In that same vein, the US Copyright Office considers that works created by animals are not entitled to registration; thus, a work must be authored by a human to be registrable. Though touted by some as a way around the problem, the US work-for-hire doctrine also falls short of providing a solution, for it still requires a human to have been hired to create a work, whose copyright is owned by their employer.

As AI systems do not have a personality that they could imprint on what they produce, authorship is beyond limits for AI.

Nevertheless, some countries (e.g. United Kingdom, Ireland, and New Zealand) do grant copyright-like protection to computer-generated works. The UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, for example, creates a legal fiction for computer-generated works where there is no human author. Section 9(3) states that “the author shall be taken to be the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.” An important nuance is that this provision assumes some form of creative intervention by a human and not autonomous, human-less generation by a computer program alone.

The originality requirement

Common law jurisdictions generally have a low threshold for originality, requiring only a minimal level of creativity or intellectual labor and independent creation for a work to be protectable. The word “originality” in that context refers to the author as being the “origin” of a work, rather than to any creativity standard.4 Some other countries, like Brazil, approach originality from the negative, and state that all works of the (human) mind that do not fall within the list of works that are expressly defined as “unprotected works” can be protected.

Under EU law and case-law, a work is original if it reflects the “author’s own intellectual creation,”5 i.e. the expression of the author’s personal touch and the result of free and creative choices. In short, both EU and US law establish the need for the work to be the proximate (direct) causal result of human action. This implies that AI, as it is currently understood as intelligence completely implemented via computational means, cannot make free and creative choices on its own and that the concept of creativity is not applicable to machines.

Economics of AI-generated outputs: incentives, markets, and monopolies of exploitation

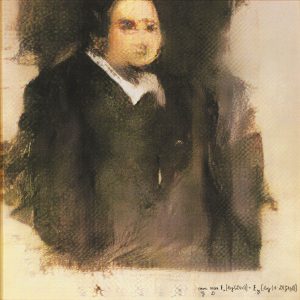

A generative adversarial network portrait painting constructed in 2018 by the collective, Obvious. It was the first artwork created using AI to be auctioned at Christie’s. Access it here.

Leaving aside theories of copyright protection and the rather abstract concepts of authorship and originality (and the even more hypothetical issue of machines having a personality and owning intellectual property rights), the real question we should ask ourselves relates to the economic environment around AI-generated content. Is there any market for AI-generated content? Do people really want to listen to Nirvana-esque algorithm-produced music or Google’s Deep-mind AI piano prowess, get immersed in the writings of a literary robot, or hang a computer-generated Rembrandt, a nightmarish Van Gogh-reminiscent Starry Night or a blurry portrait of a fictional aristocrat in their living room, not to mention to have to pay for any of that? And if so, would AI-generated products truly compete with artistic and literary works produced by humans, as substitute goods? Would the billions of AI-generated outputs produced faster than any human could produce or even consume, need any exclusivity (which is artificially inseminated in the market by means of a copyright “monopoly” of exploitation) to avoid market failure?

Of course, AI-technology developers might expect to be incentivized to invest in innovation, research, and development to help solve the world’s problems and to make AI as useful to society as possible. But copyright protection of the “artistic” outputs by an AI system is not the appropriate mechanism to stimulate this development. Unfair competition and patent law (and to a certain extent, existing copyright law protecting software as literary works) are far better suited to stimulate innovation and ensure a return on investment for the development of AI technology.

AI needs to be properly explored and understood before copyright or any intellectual property issues can be seriously considered.

All said, as much as AI has advanced in the past few years, there exists no clarity, let alone consensus, over how to define the nascent and uncharted field of AI technology. Any attempt at regulation is premature, especially through an already over-taxed copyright system that has been commandeered for purposes that extend well beyond its original intended purposes. AI needs to be properly explored and understood before copyright or any intellectual property issues can be seriously considered. That’s why AI-generated outputs should be in the public domain, at least pending a clearer understanding of this evolving technology.

In the second part of this series, “Artificial Intelligence and Creativity: Can Machines Write Like Jane Austen?” we look at two practical examples of an AI system generating “novel” content and apply the copyright eligibility criteria explained above.

Notes

1. There is as yet no widely accepted definition of “artificial intelligence.” We thus discuss this matter in general terms, and consider, strictly for the sake of discussion, that artificial intelligence is intelligence, or a simulation of intelligence, which is implemented via an automated machine, such as a digital computer.

2. Information Society Directive, 2001/29/EC.

3. Case C-145/10, Eva-Maria Painer v Standard Verlags GmbH 1 December 2011, Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

4. For US case law on the concept of originality, see Alfred Bell & co. v. Catalda Fine Arts, Inc. 191 F2nd, Baltimore Orioles Inc. v. Major League Baseball Players Association, 805 F2nd 663 (7th Cir. 1986) and Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 US 340 (1991).

5. Council Directive 2009/24/EC, Art 1(3), protection of computer programs as “the author’s own intellectual creation”; Database Directive 96/9/EC, Art 3(1); Case C‐5/08, Infopaq, ECLI:EU:C:2009:465; Information Society Directive, 2001/29/EC.

?: Featured image is “Love Art Science 95” by Kollage Kid, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Posted 10 August 2020